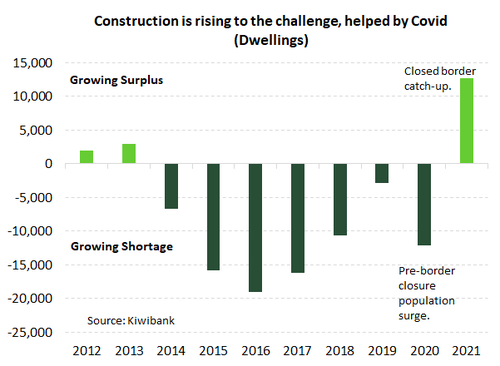

- In a rare silver lining to the Covid crisis, NZ has for the first time in 8 years produced a surplus of homes. With a drop in population growth, builders are catching up.

- But the 13,000-home surplus generated last year only nibbles around the edges of NZ’s huge shortage. Which we estimate to be in the order of 67,000 houses.

- We estimate that it will take at least three years to balance the market, dependent on when, and how, our border fully reopens.

- Balancing the housing market with more affordable dwellings is the best way to tackle affordability and widening inequality. Allowing the supply of dwellings to better respond to future demand is key to success.

For the best part of the last decade, population growth has far outstripped the supply of new homes. NZ simply hasn’t built enough homes to absorb the record number of migrants coming to our shores. But Covid has changed that, at least temporarily. We estimate that for the first time in eight years NZ has managed to produce an annual surplus of around 13,000 homes. But before getting carried away, the surplus in the 12 months-to-March just eats into our massive housing shortage, which we now estimate to be 67,000 homes. And that’s still a shortage the size of the Hawke’s Bay. There is also a sad irony to the 2020 housing surplus. It took one crisis (Covid-19) to help alleviate another (a chronic shortage of houses). The closure of the border over 2020 occurred as residential construction was fast gathering pace. Nevertheless, we look at the silver lining here. Covid-19 has provided a rare opportunity to make a meaningful dent in our housing shortage. It’s an opportunity that still presents itself. We expect NZ’s border to remain closed – bar a limited number of quarantine free travel bubbles – well into 2022.

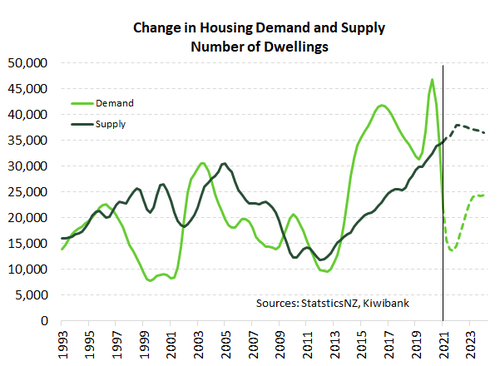

Based on our projections, NZ’s accumulated housing shortage will fall further this year and next. More importantly, we estimate that housing supply and demand could finally balance some time in 2024. However, the outlook is highly uncertain. Future demand for housing will be dependent on our border fully reopening. And when the border does reopen, will there be a flood of arrivals or a hesitancy to cross borders? On the supply side, capacity constraints are ever present, and a slowing housing market may also take the heat out of home building.

Despite an opportunity to finally balance the housing market, there remains a longer-term issue. The supply of housing is far too slow to respond to changes in demand. The investment in new infrastructure isn’t keeping up with the current rate of home building. And that’s on top of the mountain of upgrades required to existing infrastructure. The Government’s recent announcement of a Housing Acceleration Fund for local housing-related infrastructure is a welcome move. But, as we have already said, the $3.8bn fund is merely a drop in a leaky bucket. Also, Kiwi need to build up not just out. Densification is often blocked by vested interests winning out over the collective benefit of building homes closer to where the most productive jobs are located – the centres of our largest cities.

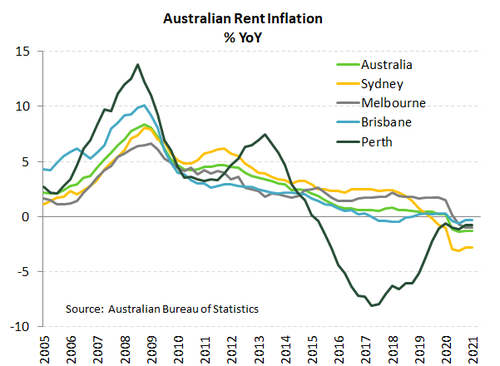

Renters are often overlooked when considering the housing market. And it has been claimed that tax changes to make interest payments of property investors a non-deductible expense will see rents surge. We’re not convinced. Rents can only increase by as much as the market can bear. And rents were already on the ascent for a host of reasons. In any case, the introduction of rent controls would be a poor policy choice to battle the rising cost of accommodation. Evidence from overseas shows that such controls reduce the stock of rental property and benefit existing tenants at the expense of future ones. An increase in the supply of rental property is a far better remedy. Australia proves that if you build the supply, rents can ease.

Renters are often overlooked when considering the housing market. And it has been claimed that tax changes to make interest payments of property investors a non-deductible expense will see rents surge. We’re not convinced. Rents can only increase by as much as the market can bear. And rents were already on the ascent for a host of reasons. In any case, the introduction of rent controls would be a poor policy choice to battle the rising cost of accommodation. Evidence from overseas shows that such controls reduce the stock of rental property and benefit existing tenants at the expense of future ones. An increase in the supply of rental property is a far better remedy. Australia proves that if you build the supply, rents can ease.

A balanced housing market is now within reach

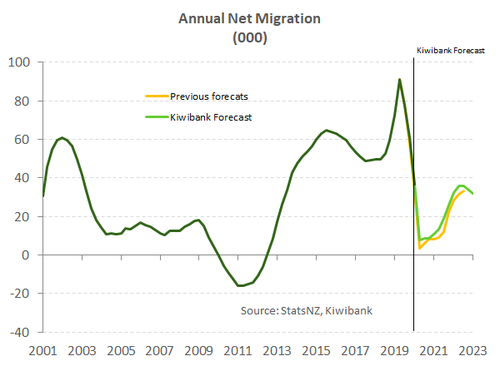

The tide looks to have turned in NZ’s battle to defeat the housing crisis. In the year to March 2021 we estimate there was a surplus of 13,000 homes built. However, it’s far too early to pop open the champagne. The surplus only dents the shortage that has built-up over years. Our previously estimated shortage of 80,000, now comes in at 67,000. Ironically, our ability to generate a surplus of houses in the last year was largely due to Covid. Our closed border has meant net migration has almost evaporated, leading to a fall in the demand for new housing. After peaking at 90,000 people in the year to March 2020, net migration added only a tenth of that figure to NZ’s population this year (see chart below). At the same time, the supply of new housing continues to rise. We’ve experienced the fastest rate of growth in supply since the 1970s, and supply growth continues to accelerate.

A time when we will no longer have a housing shortage now looks to be within reach. Aotearoa’s border remains closed and is unlikely to fully open until next year, at the earliest. Crucial to reopening will be the success of NZ’s Covid-19 vaccination programme. We are hopeful the border fully opens by the middle of 2022. On the supply side, recent building consents suggest the pace of building will rise further over the year ahead. We have pushed the envelope of our housing supply and demand model to provide an estimate of when the housing shortage will be addressed. At some stage in 2024, supply should meet demand. And depending on appetite on both sides, we may see the accumulation of an oversupply. That’s increased affordability.

On the demand side, population growth is the key driver. And the biggest driver of NZ’s population growth is net migration. We have revised our net migration forecast. The new projection is slightly higher. Because the quarantine-free travel bubble with Australia makes it easier to move across the Tasman. And the travel bubble is set to open more capacity in managed isolation facilities. We then expect net migration to rise sharply from about the June quarter next year, when the border is expected to fully reopen. A pent-up desire to move to NZ (for instance, past working visa holders) is probable. We have assumed that net migration will settle near the new long-term average of 30,000, well below the last peak. Obviously net migration could come in well above, or well below, these estimates depending on policy.

There is significant uncertainty around net migration forecasts, and hence the timing to the end of the housing crisis. Globally, there might be hesitancy to move across borders in fear of another pandemic stranding people from friends and family. Or demand to move to NZ may surge as we are viewed as a South Pacific oasis, void of the Covid-19 tragedies that have hammered much of the rest of the world – extending the housing crisis.

There is significant uncertainty around net migration forecasts, and hence the timing to the end of the housing crisis. Globally, there might be hesitancy to move across borders in fear of another pandemic stranding people from friends and family. Or demand to move to NZ may surge as we are viewed as a South Pacific oasis, void of the Covid-19 tragedies that have hammered much of the rest of the world – extending the housing crisis.

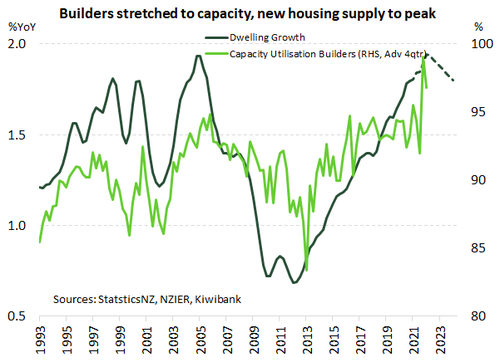

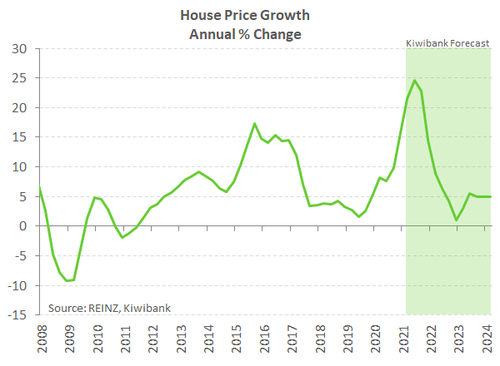

On the supply side, residential consents are at multi-decade highs. Consents point to a further acceleration in NZ’s housing stock over 2021. However, the current construction boom looks to be approaching the peak in the current cycle. Beyond 2021, we see the growth of new housing stock slowing. NZIER’s latest quarterly survey of business confidence revealed that capacity utilisation among builders is running well past the red line (see chart above). Accelerating house prices also provides property developers with the confidence they can sell new builds for a profit in the future. However, house price growth is expected to cool from the second half of 2021.

We believe there is enough momentum in the market – with its chronic shortage of listed property – to see house price growth peak at around 25%yoy in the current quarter. However, affordability constraints, new housing supply, and recent policy changes are expected to start taking the heat out of the market. The return of LVR restrictions on investor mortgages on their own may not have been enough to tip the balance. The recent surge in house prices has helped to push up investors’ equity on existing portfolios. Equity that can be used as a deposit for additional borrowing. However, combined with recently announced tax changes, policy should pack somewhat of a punch on the investor side of the market. Overall, we see a deceleration in house price growth this year and next, hitting a low of 1%yoy by the end of 2022. Recent developments mean that even if the RBNZ is given the OK to have DTI restrictions and restrictions on interest only lending in their macroprudential toolkit, the Bank may no longer need to use them. Certainly not immediately anyway.

Unfortunately, the current housing crisis has supercharged rising inequality. And while a reduction in the housing shortage is encouraging to see, we still have not addressed a fundamental issue. Housing supply is simply far too slow to respond to changes in demand. The current shortage goes hand-in-hand with a lack of new housing-related infrastructure. The Government’s announcement of the Housing Acceleration Fund is welcome but long overdue. Unfortunately, at just under $4bn it feels a little underdone. The Government’s Budget on May 20th might have more to add – we certainly hope so. And the fund ignores the years of underfunding of existing infrastructure in many of our older cities. Densification of housing will be hampered if infrastructure is not up-to-scratch. Finally, more needs to be done to speed up and lower the cost of construction. A revamp of the Resource Management Act is certainly part of the solution. If housing supply remains too rigid in the future, then we are likely to see a case of history repeating itself.

Renters need affordable accommodation too

An unintended consequence of the Government’s housing policy announcement is the possibility of significant rent hikes as landlords try to recoup losses. Rent hikes are not ideal amidst a housing affordability crisis. However, like any market, the price (rent) is determined by supply and demand rather than arbitrary threats from suppliers. Unless of course the industry is dominated by only one supplier as is the case of a monopoly. On the demand side, rent hikes are constrained by what tenants can afford, which in turn is limited by income growth. Importantly, a vacant rental is far more costly to a landlord than a lack of interest payment deductions.

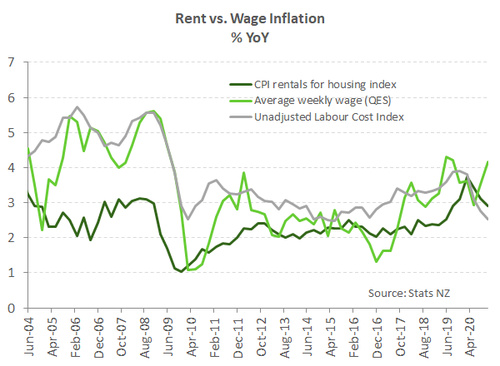

According to the CPI measure, general rent inflation peaked at the start of 2020 at 3.7% yoy. Since then rent inflation has eased, falling back to 2.9% by the end of 2020 – pulled down by the last year’s Covid-related rent freeze. Nevertheless, rent rises were already on the cards with the rent freeze no longer in play, recent healthy homes requirements, and a general shortage of rentals. We don’t think tax changes will add significantly to rent inflation that was already on its way.

According to the CPI measure, general rent inflation peaked at the start of 2020 at 3.7% yoy. Since then rent inflation has eased, falling back to 2.9% by the end of 2020 – pulled down by the last year’s Covid-related rent freeze. Nevertheless, rent rises were already on the cards with the rent freeze no longer in play, recent healthy homes requirements, and a general shortage of rentals. We don’t think tax changes will add significantly to rent inflation that was already on its way.

There are some suggestions that if rents do rise as a result of recent policy changes, some form of rent control should be introduced to soften the blow to renters. Any form of rent control would be a terrible policy choice to make. Empirical evidence in the United States show that while existing tenants benefit from clipped rent inflation, there is an overall large net cost to society. Firstly, rent controls reduce the incentive for developers to renovate existing or build new rentals. And rent controlled properties are so coveted, that new tenants are locked out of affordable housing. The outcome in NZ is likely to put even more pressure on social housing waiting lists. A better solution is to ensure that new supply of both rentals and owner-occupied housing has as little hinderance as possible. And boosting the supply of rentals does curtail excessive rent rises, as seen recently in many of Australia’s major cities.

A glut of new apartments in many of Australia’s major cities contributed to falls in rents. And the only viable way to reduce rents in New Zealand, is to boost supply. Like a shortage though, a glut in housing brings its own problems. Ultimately when it comes to housing, it’s all about balance.