- With the exception of a few travel bubbles, the drawbridge into NZ has stood upright for two years. But the Govt has now laid out the roadmap towards a full reopening to the rest of the world.

- NZ’s reopening will provide some comfort for the tourism and education sectors. But given the phased timing, we see a net 20k people emigrating from NZ by the end of the year.

- A net outflow is likely to exacerbate the labour shortages present in the labour market. And alongside Omicron, falling house prices, rising inflation and higher rates, 2022 is shaping up to be a challenging year for the NZ economy.

Only one quarter in and 2022 is already proving to be another challenging year for the NZ economy. NZ is contending with the omicron wave of covid-19, rapidly rising inflation, a housing market in retreat, and the steady tightening of monetary policy. All of which are expected to hit spending and weigh on GDP growth this year. In our most recent forecast, we see growth over 2022 slow to 3% from 2021’s 5.6% jump.

Yet another factor that will have some bearing on the performance of the economy will be the opening of the border. Not only will the reopening provide some comfort for tourist operators and education providers, but it will see NZ’s population once again be thrown around. We see a net 20,000 people emigrating from NZ by the end of 2022 due to the phased opening of the border. A net outflow this year is likely to exacerbate the labour shortages present in the labour market.

Population growth to slow further before recovering.

Population growth is an underpinning driver of economic growth. Including, as an input into household consumption growth and growth in labour supply among others. But as Aotearoa gradually reopens to the rest of the world post-covid, NZ’s population growth is expected to fall further before ultimately recovering.

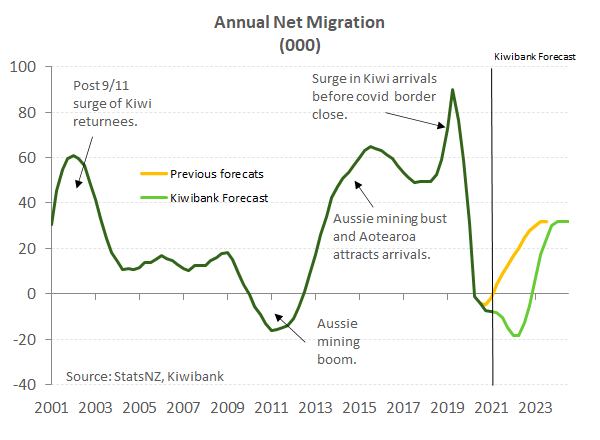

Like most developed nations, an aging population and falling fertility rates mean NZ’s natural population growth struggles to keep our head count increasing over the long-term. On its own, structurally weak natural population growth throws up some daunting challenges. Just look at Japan for instance, which has suffered decades of deflation and anaemic growth. However, a lack of local population growth is typically offset by net migration here in NZ. Net migration is the difference between longer-term arrivals to, and long-term departures from NZ. The pandemic led to closed borders and the drying up of net migration almost overnight. And NZ is at present experiencing a small outflow of around 8,000 people per annum – the last time NZ recorded annual net outflows was back in 2013.

The Government has laid out the roadmap towards NZ’s borders fully reopening to the rest of the world. NZ citizens can already enter the country without the need to self-isolate. From the 12th of April our Aussie mates can do the same – in addition to people on temporary work and student visas. From May, other visa waiver countries will follow Australia. And by October, the border will fully open to all visa categories. At present, arrivals are still subject to pre-departure covid tests, and the requirement for RATs within the first week of arrival. The roadmap is certainly welcomed by tourist operators and education providers. The Government’s roadmap is subject to change of course. The planned opening of the border to Australians has already been brought forward for instance.

The phased timing of the border reopening is expected to throw the net migration figures around over the next 12-18 months. Long-term departures are forecast to increasingly exceed arrivals over 2022. The assurance that Kiwi moving overseas can return home without the need for MIQ is expected to rekindle the desire for the big OE. Annual net migration outflows could reach 20,000 by the end of the year. That’s similar to the last period of major outflow seen back in 2011, when an Aussie mining boom attracted Kiwi across the ditch for prospect of a six-figure salary.

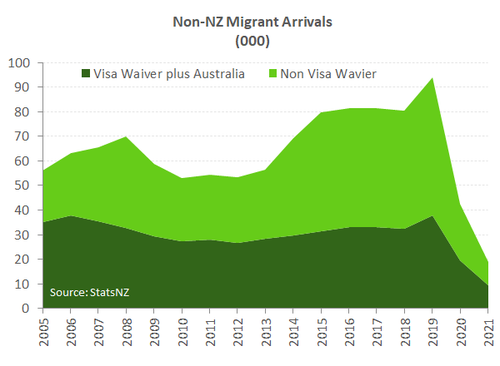

Long-term arrivals in contrast will be held back by the gradual reopening. Prior to covid, the top three sources of non-NZ arrivals were China, India, and South Africa. And all three are not visa waiver countries. In fact, applying current visa-waiver settings to non-NZ migrant arrivals data shows that most arrivals pre-covid came from non-waiver countries (see chart below). The border will reopen to these countries from the December quarter. In the meantime, arrival numbers will be held back. From the December quarter we are picking long-term arrivals will start to meaningfully lift, and eventually lead net migration to return to an average of around 30,000 people per annum. That’s higher than the long-term average, but well down from pre-covid highs.

Long-term arrivals in contrast will be held back by the gradual reopening. Prior to covid, the top three sources of non-NZ arrivals were China, India, and South Africa. And all three are not visa waiver countries. In fact, applying current visa-waiver settings to non-NZ migrant arrivals data shows that most arrivals pre-covid came from non-waiver countries (see chart below). The border will reopen to these countries from the December quarter. In the meantime, arrival numbers will be held back. From the December quarter we are picking long-term arrivals will start to meaningfully lift, and eventually lead net migration to return to an average of around 30,000 people per annum. That’s higher than the long-term average, but well down from pre-covid highs.

Curing cabin fever means an even tighter labour market

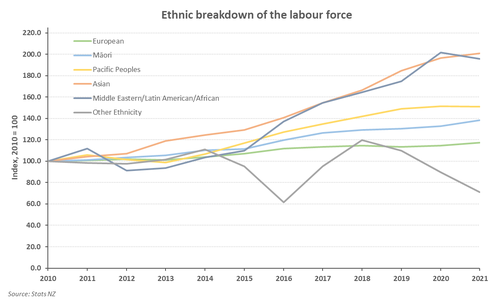

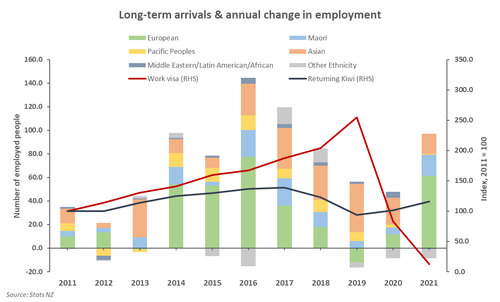

Prior to the pandemic, long-term arrivals were a key source of labour. The number of migrants entering NZ on a work visa had been on a steep growth trajectory. And the rise in migrants saw a growing proportion of other ethnicities entering the labour force. While the European ethnic group remains the largest in the labour force (64%), its proportion has been declining. In contrast, the Asian ethnic group is among the fastest growing – second only to the Middle Eastern & Latin American ethnic group which has seen 70% growth between 2014 and 2019, though accounts for just 1% of the labour force. Over the five years prior to covid, those in the labour force of Asian ethnicity have grown from 293,000 to 433,000 – that’s a 48% increase.

force. While the European ethnic group remains the largest in the labour force (64%), its proportion has been declining. In contrast, the Asian ethnic group is among the fastest growing – second only to the Middle Eastern & Latin American ethnic group which has seen 70% growth between 2014 and 2019, though accounts for just 1% of the labour force. Over the five years prior to covid, those in the labour force of Asian ethnicity have grown from 293,000 to 433,000 – that’s a 48% increase.

The turn of the decade marked the beginning of the covid pandemic and the end of the migration boom. With the exception of a few travel bubbles here and there, the drawbridge into NZ has stood upright since March 2020. For the past two years only NZ citizens have been allowed to enter. As expected, the number of long-term arrivals on a work visa fell off a (steep) cliff). And at the same time, the downward trend of returning Kiwi (long-term arrivals of NZ citizens) pivoted, with more coming back home.

Changes to the migration landscape has had a ripple effect on the ethnic make-up of the labour force. Since 2020, there have been relatively fewer non-European people enter employment compared to previous years. Over 2021, 69% of the 88,000 newly  employed identified as European, 20% were Māori, and 19% were Asian. So-called “Fortress NZ” is in stark contrast to 2019 when there was a 12,200 drop in European employment and 73% of the newly employed were of Asian ethnicity.

employed identified as European, 20% were Māori, and 19% were Asian. So-called “Fortress NZ” is in stark contrast to 2019 when there was a 12,200 drop in European employment and 73% of the newly employed were of Asian ethnicity.

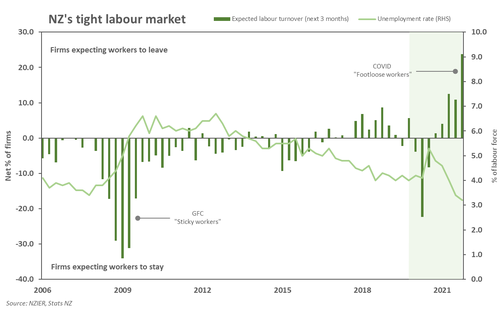

With the closed border, labour shortages have been an issue that’s front and centre for many firms. The pool of available workers has been limited to homegrown talent – and it’s quickly evaporating. But leading indicators suggest that demand for labour remains robust. Hiring intentions have intensified, job vacancies are well above pre-Covid levels and expected labour turnover has hit a 50-year high. Employees are leveraging their newfound bargaining power to switch jobs and secure large wage increases and/or better benefits. For some firms, there’s pressure to automate given the scarcity of workers. First highlighted in the March 2021 quarter business survey, NZIER reported a growing proportion of firms intending to invest more in labour-saving technology. The change in investment strategy underscores our long-standing reliance on migrant labour and thus our underinvestment in technology.

highlighted in the March 2021 quarter business survey, NZIER reported a growing proportion of firms intending to invest more in labour-saving technology. The change in investment strategy underscores our long-standing reliance on migrant labour and thus our underinvestment in technology.

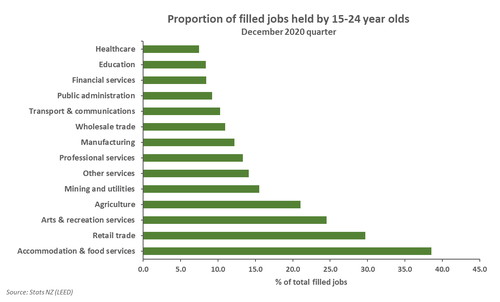

But in the meantime, migrant labour is needed to alleviate the pressure on the labour market. Unfortunately, conditions may get worse before they get better. Our border is set to gradually re-open this year. As mentioned above, we expect to lose ballpark 20,000 people as we first reopen to Australia and visa-waiver countries. With fewer people booking one-way tickets to NZ, the outflow will only add further stress on the labour market. And some sectors are at greater risk than others. With young Kiwi more of a flight risk, hospitality in particular may be most affected. Across all industries, accommodation & food services, retail trade, and arts & recreation are the biggest  employers of young people. Within accommodation and food services, 15-24 year olds account for over 38% of the workforce.

employers of young people. Within accommodation and food services, 15-24 year olds account for over 38% of the workforce.

The outflow of Kiwi certainly puts downward pressure on the unemployment rate. However, a skills shortage and mismatch will mean an unemployment rate in the 2% range will be difficult to sustain, let alone achieve. The shrinking pool of available skills will mean some job vacancy posts will just continue to catch dust. Given the migration trends pre-covid, we may not see the long-term arrivals from China, India, South Africa etc and fill those vacancies until next year. We expect the labour market to remain incredibly tight for some time yet. Wage growth may even rise higher than we originally forecast as employers do all they can to attract, and perhaps most importantly, retain staff. It’s not just us facing a tight labour market. The US, UK, Canada and Australia, to name a few, are also experiencing a ‘Great Resignation’. But these countries are offering relatively higher wages and relatively more affordable housing. We’ve got some tough competition.

But one of the brighter aspects of the unfolding net emigration story, is that the high demand for workers means that those in employment are in the safe zone. And secured employment should continue to support household consumption. Although given soaring inflation and greater sensitivity to rising mortgage rates, we are unlikely to see the same spending habits of 2020.