But some things are still in fashion.

- Substantial gains in education: as female participation has skyrocketed. But the pigeonholing of students has stood the test of time.

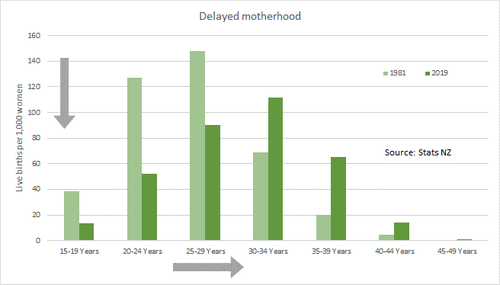

- Greater labour force participation: but a new trend has emerged: delayed motherhood. And it’s raising red flags around current policy.

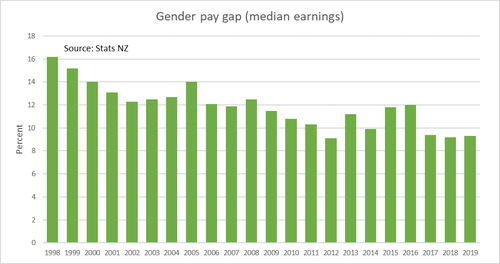

- Rising incomes: has narrowed the gender pay gap with more women involved. But it’s still a gap. And the current tax system is making things worse.

Much has changed since the 1970s. From flared jeans to frayed jeans, ‘fros to bobs and ABBA to Adele. Women’s experience in the New Zealand economy is no different. We’ve witnessed: substantial gains in education; greater labour market participation; and rising incomes. Women’s economic status has improved since the days of the Hippie – there’s no denying it. But 50 years on, some things are still in fashion. Progress is slowing, and we need to find ways to regain momentum.

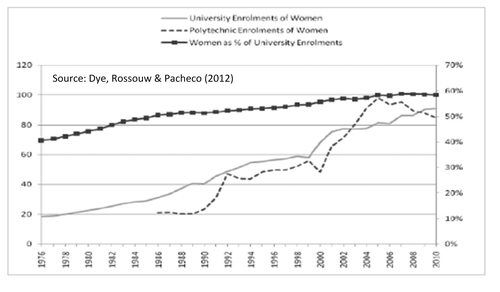

Female participation in education has skyrocketed. Women have traded in their typewriters for textbooks. And women now make up majority of enrolments. But, by and large, the pigeonholing of students seen in the 70s has stood the test of time. It’s not surprising that men and women continue to cluster in the labour market. More work needs to be done to break it up. Solution: Careers day with a diverse panel of industry representatives.

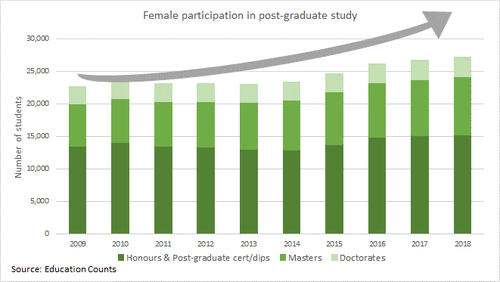

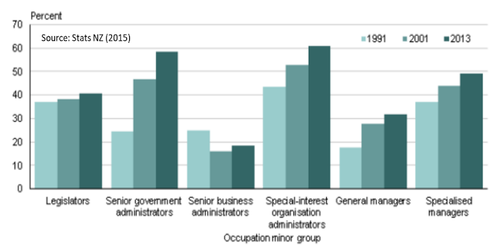

The rising popularity of postgraduate study has boosted women to higher rungs on the career ladder. It’s more common today to see women in the boardroom. The number of female directorships among the top 100 listed companies has grown from 8.7% to 24.1%. But it took a decade. And 24.1% tells us that there’s plenty of room in the boardroom. Solution: Targeted post-graduate scholarships.

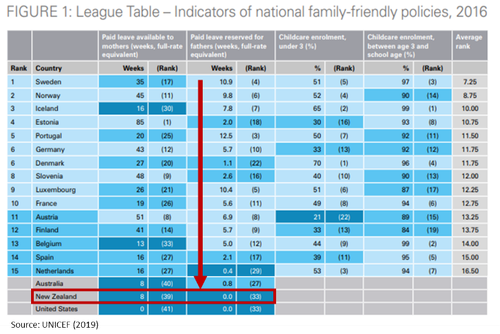

In 1971, the female labour force participation rate was 39%. Fast forward five decades and over two-thirds of working age women (65.6%) are active in the labour force. The rise in the employment rates of “rugby mums” is most striking. A new trend has emerged: delayed motherhood. But it’s not necessarily a good thing. Rather, the trend raises red flags around our parental leave legislation. The difficulty in sharing leave between parents may be one driver of the new trend. It’s clear that family formation remains highly influential on women’s employment. Just take a look at their high part-time employment rates. To achieve a more equitable workforce we need to adopt a more equitable approach to parenthood. Solution: Paternal leave and workplace childcare.

As women have become more involved in the economy, the gender pay gap has narrowed. But its disappearance remains elusive. For the past 20 years, the earnings gap has fluctuated between 10% and 14%, albeit a vast improvement from 17% in the 1990s. And for women in low income households, in particular, the New Zealand tax system is making things worse. Solution: Re-valuation of “women’s work” and a re-structure of the tax system.

Women’s economic status has reached new heights. But progress is incomplete. We need to keep the momentum going. But doing so will come at a price: careers day events and scholarships require funding; extending paternity leave will cost a tidy sum; establishing workplace childcare may eat into company profits; a re-valuation of “women’s work” won’t be cheap; and a re-structure of the current tax system will likely cause a few headaches. But does the need to ensure women are participating in the economy as much as they desire, justify the expense? Of course. Kiwibank experience shows the benefits of making a workplace more attractive to women. It’s time to clean out the closet.

A higher aptitude sets a higher altitude

Any parent would agree, teenagers are an angsty bunch. Young people generally don’t do well with authority. But unlike James Dean, young girls have been rebels with a cause. Especially when it comes to education.

Any parent would agree, teenagers are an angsty bunch. Young people generally don’t do well with authority. But unlike James Dean, young girls have been rebels with a cause. Especially when it comes to education.

Back in the day, clerical and sales-type employment was the #1 destination for female school leavers. With time, the pendulum has swung. Today, more women pursue higher education. The first chart shows a welcome decline in the employment rate of young women. The second chart shows the rise in tertiary enrolments.

Admittedly, institutions have helped. In 1991, science, maths and technology were made compulsory in secondary school – subjects in which females have traditionally been absent. The exposure to a wider range of subjects encouraged more young women into advanced study. Today, women are just as likely as men to hold a science degree; a medical student is equally likely to be either male or female; and both men and women are battling it out in the mock trials.

Admittedly, institutions have helped. In 1991, science, maths and technology were made compulsory in secondary school – subjects in which females have traditionally been absent. The exposure to a wider range of subjects encouraged more young women into advanced study. Today, women are just as likely as men to hold a science degree; a medical student is equally likely to be either male or female; and both men and women are battling it out in the mock trials.

The field of study carries implications for future occupations. Because for most (abstracting from the “Branson”s and “Chanel”s of the world), education precedes occupation. Case in point – the entry of women into male-dominated occupations follows the entry of women into male-dominated disciplines. The rapid rise of the female scientist, for example, links back to compulsory study in school. The same goes for law, medicine and commerce. Men were once the incumbents, but women have swarmed onto the scene.

Unforuntely, outside of the big three – law, medicine and commerce – the clustering of men and women in the labour market is still apparent. Women make up 47.7% of the employed workforce. If men and women were equally distributed across all occupations, we would expect 47.7% of workers in each occupation to be female. This is not the case. Administrative workers are overwhelmingly female (75%). And technicians and trade workers are overwhelmingly male (80%).

The clustering is fundamentally an issue at the education level. By and large, the pigeonholing of students is evident – bar the big three. Young girls are told they’ll make great caregivers, nurses and teachers. To be a Silver Fern is the be-all and end-all. But with the rise of robots upon us, there’s strong impetus for girls to deepen their footprint in STEM subjects. In fact, civil engineers, science technicians and software developers are among the most in-demand jobs – jobs traditionally held by men. Currently, women are outnumbered four-to-one in engineering workshops and three-to-one in computer labs.

Young boys are given the same treatment. They’re seen as better tradies, pilots and engineers. They dream of being an All Black. For decades, male representation has been lacking in teaching, health (excluding medicine) and the arts. Shortland Street Hospital may only exist on our television screens, but it echoes real life for male nurses.

It’s clear that we need to break up the clustering. But it’s even clearer that the best place to start is in the classroom.

Solution: Careers day

It’s a matter of perception

We can influence where young boys and girls will end up, by influencing how they begin. Just as in 1991, we need to continue broadening their career optoions. To shift occupational preferences, we need to shift study preferences. And to shift study preferences, the concept of “men’s work” and “women’s work” needs to be more fluid. Men should be seen as great carers and women as great builders.

We can influence where young boys and girls will end up, by influencing how they begin. Just as in 1991, we need to continue broadening their career optoions. To shift occupational preferences, we need to shift study preferences. And to shift study preferences, the concept of “men’s work” and “women’s work” needs to be more fluid. Men should be seen as great carers and women as great builders.

So organise a careers day at your children’s school. And bring in industry representatives of the opposite gender. Better still, both genders. Take President and COO of Space X, Gwynne Shotwell, for example. Shotwell’s path to becoming one of the world’s most successful engineers began with hearing from a female mechanical engineer – “She was doing really critical work, and I loved her suit. And that’s what a 15-year-old girl connects with.”

Rising through the ranks

The rising popularity of postgraduate study has seen the number of women in managerial positions grow from 32% in 1991, to 45% in 2013. It’s more common today to see women in the boardroom. Female attendance is particularly high within special interest organisations and government agencies – sectors in which female employment has historically been high. But there are few senior female business administrators within private organisations. In 2008, women held 8.7% of directorships among the top 100 listed companies. Today, that percentage has grown to 24.1%. But it took a decade. The proportion of women in more senior roles may be rising, but the climb is proving to be a hike.

The rising popularity of postgraduate study has seen the number of women in managerial positions grow from 32% in 1991, to 45% in 2013. It’s more common today to see women in the boardroom. Female attendance is particularly high within special interest organisations and government agencies – sectors in which female employment has historically been high. But there are few senior female business administrators within private organisations. In 2008, women held 8.7% of directorships among the top 100 listed companies. Today, that percentage has grown to 24.1%. But it took a decade. The proportion of women in more senior roles may be rising, but the climb is proving to be a hike.

Solution: Scholarships, not quotas

A bottom-up solution for a top-level problem

One way to fast-track gender equality at the leadership level, is through gender quotas. However, many – including women – recoil at the idea of implementing quotas. Because stigma is a parasite to the system. A helping hand may regard women as being less qualified and could undermine the legitimacy of their rise through the ranks. Women want to be recognised for their skills and capabilities. And it is their ability to add value that earns them a seat at the boardroom. Not because they have one extra X chromosome.

One way to fast-track gender equality at the leadership level, is through gender quotas. However, many – including women – recoil at the idea of implementing quotas. Because stigma is a parasite to the system. A helping hand may regard women as being less qualified and could undermine the legitimacy of their rise through the ranks. Women want to be recognised for their skills and capabilities. And it is their ability to add value that earns them a seat at the boardroom. Not because they have one extra X chromosome.

Efforts may be better directed toward ushering more women into the boardroom, rather than closing the door on those deserving of a seat. To solve the top-level problem, a bottom-up approach is best. And bottom-up meaning education (again). Targeted scholarships could provide incentive for girls to sit in classrooms they would otherwise walk past. The RBNZ, for example, offers the Women in Central Banking Scholarship. Females are encouraged into post-graduate study in areas including economics, finance and maths. And a guaranteed position at the RBNZ gets their feet in the door.

Scholarships offered at the post-graduate level would certainly help women become leadership-ready. Indeed, the correlation between the rise of women in top positions and the rise of women in higher education is no coincidence. Scholarships may not be the speedy solution that affirmative action, like quotas, offers. But education can be a pretty powerful tool to smash the glass ceiling.

Working nine to five

The female presence in the New Zealand labour market is growing. In 1971, the female labour force participation rate was 39%. Fast forward five decades and two-thirds of working age women (65.6%) are active in the labour force. And we’re not excluding our golden girls from the bunch. Women aged 60 years and over are showing little signs of slowing down. The abolishment of a compulsory retirement age in 1999 encouraged women to postpone retirement. Increased life expectancy, particularly among women, has been another labour market helping hand.

But the most significant change in participation has been among the “rugby mums”. In the 70s and 80s, male and female employment rates were closest in the youngest age groups. But rates diverged during the typical “parenting” years. The age-old narrative continues today. But the recent shallowing out of the dip (see above chart) suggests a new trend: delayed motherhood. More women are postponing having children to their mid- to late-30s.

But the most significant change in participation has been among the “rugby mums”. In the 70s and 80s, male and female employment rates were closest in the youngest age groups. But rates diverged during the typical “parenting” years. The age-old narrative continues today. But the recent shallowing out of the dip (see above chart) suggests a new trend: delayed motherhood. More women are postponing having children to their mid- to late-30s.

Along with ‘staches, bell-bottoms and discos, the 70s saw the rise of the women’s liberation movement. The 19th century ideology that largely dictated the extent of women’s involvement in the economy quickly became antiquated. Women challenged the notion that their economic value was inextricably linked to their ability to bear children. It was seen as important for women to finish their education, step outside the secondary sector, and establish a career.

But it’s not all hunky dory. Delayed motherhood is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, the trend reflects greater involvement in the economy. So women’s financial position and material wellbeing are better off. And children are given a relatively better start in life (at least financially). But at the same time, our population is rapidly greying. Delayed motherhood is contributing to the decline in fertility. Not to mention women’s health from having children later in life. We’ve been covering up the grey with a cheap hair-dye in the shade ‘migration’. But the long-term demographic challenges require more than migrants.

Delayed motherhood is a fact. And it highlights the influence family formation has on women’s employment. There’s no doubt that balancing paid and unpaid (domestic) work presents several difficulties. And women are the stars of this balancing act. The 2009-10 New Zealand Time Use Survey revealed that women spent more than twice the time men spent on childcare each day. A “second shift” it’s called. For women trying to balance work and family commitments, flexible and part-time arrangements are attractive options. And oftentimes, the only option.

Delayed motherhood is a fact. And it highlights the influence family formation has on women’s employment. There’s no doubt that balancing paid and unpaid (domestic) work presents several difficulties. And women are the stars of this balancing act. The 2009-10 New Zealand Time Use Survey revealed that women spent more than twice the time men spent on childcare each day. A “second shift” it’s called. For women trying to balance work and family commitments, flexible and part-time arrangements are attractive options. And oftentimes, the only option.

Women’s high part-time employment rates give new meaning to untapped labour. There’s a clear desire to work more. But for reasons including childcare, they are restricted to do so. In fact, women may be choosing to delay having children because of the difficulty in sharing leave with their partners.

The Parental Leave and Employment Protection Act 1987 was enacted to support the changing roles of men and women within and beyond the home. But its success is questionable. It’s clear that women still shoulder the majority of family responsibilities. To achieve a more equitable labour force, we need to adopt a more equitable approach to parenthood. While current legislation reflects this in principle, it’s falling short in execution. And it comes down to (poor) design. All paid parental leave is allocated to the primary carer, and women are named by default. Parental leave and maternity leave are effectively one and the same. Unless mothers transfer their leave, fathers are left with just two weeks unpaid leave. So even if men wanted to assume a greater role in the home, the apron just doesn’t fit.

The end goal is to have it both ways – to boost female hours worked, but not at the expense of delaying motherhood.

Solution: Paternal leave

“Mummy’s home!!!” (Daddy’s already home)

New Zealand can claim a number of world firsts. We’re the first country to give women the right to vote. The first country to offer a state pension. And the first country to adopt a standard time nationwide. But when it comes to paid parental leave, we’re tied for third worst. According to a recent United Nations report, we only top the United States which has no federally mandated policy. So we might as well be in last place. But that’s not the worst part. The worst part is, when it comes to paternal leave, we’re not even considered. And that’s the problem.

Parental leave needs to be more flexible and shared across genders. Introducing paid paternity leave can help to achieve a more level playing field at home and at work. And when men are more equal at home, women can be more equal at work.

Parental leave needs to be more flexible and shared across genders. Introducing paid paternity leave can help to achieve a more level playing field at home and at work. And when men are more equal at home, women can be more equal at work.

Perhaps we should take our cues from the Finns. Finland is the happiest country in the world, and their generous paternity leave is giving them a reason to smile. Leave reserved for fathers was raised so that they’re just as likely to be the primary carer. For both parents, there’s now equal opportunity to return to work and advance their careers.

Solution: Workplace childcare

Just an elevator ride away

The traditional family support network is weakening. But childcare is a critical factor in eliminating barriers to women’s full employment. There is a need to improve non-family childcare. And it is a need that can be met at work.

The traditional family support network is weakening. But childcare is a critical factor in eliminating barriers to women’s full employment. There is a need to improve non-family childcare. And it is a need that can be met at work.

For care of young children, an on-site crèche is a popular workplace solution. Employees would appreciate having their children just an elevator ride away. And given that it’s on-site, there’s no need to race out the door to meet the 6pm pickup time. Similarly, companies could set-up a “homework centre” where children can wait before- and after-school. For the Commonwealth Bank of Australia, workplace childcare is yesterday’s news. Employees are given priority access to neighbouring long-day corporate childcare centres.

Obviously, some companies cannot practically have a crèche or centre on-site. These companies could instead team up with childcare providers to negotiate discounts, just as they do with healthcare providers.

School holidays can be another source of worry for parents. Most employees are given four weeks of annual leave, but school holidays total 12 weeks. To help make up the difference, companies could also organise school holiday programmes and run camps.

To have facilities readily available is especially helpful when regular arrangements fall through. It can make the difference between an employee being absent or at work. In fact, along with lowered absenteeism, other potential employer benefits include improved productivity, high employee retention and reduced turnover.

But the best thing about this solution is that either parent can take up the offer. Better childcare can help both parents ensure the continuity of their careers despite having a young family.

Closing the gap

As women have become more involved in the economy, the gender pay gap has narrowed. But a trend toward zero remains elusive. Women continue to earn a fraction of men’s (median) earnings. And for the past 20 years the gap has fluctuated between 10% and 12%.

The narrow range of occupations held by women is one reason for the gap. In 2013, the 20 most common occupations among women largely comprised of “caring” occupations. And accounted for 48.2% of the female workforce. As a point of reference, the top 20 occupations among men accounted for just 37.1%. But the issue with women’s career options is that they’re typically low-paid. Tthe overrepresentation of women in low-paid industries is keeping the measure above zero.

The narrow range of occupations held by women is one reason for the gap. In 2013, the 20 most common occupations among women largely comprised of “caring” occupations. And accounted for 48.2% of the female workforce. As a point of reference, the top 20 occupations among men accounted for just 37.1%. But the issue with women’s career options is that they’re typically low-paid. Tthe overrepresentation of women in low-paid industries is keeping the measure above zero.

But in a study by the Ministry of Women, the gender pay gap was found to be 12.71% even after removing the effect of: personal (age, ethnicity), household (marital status, children), occupational, industrial and regional characteristics, as well as employment status and educational attainment. In fact, the differences in observable characteristics between men and women only explained 16.9% of the gap.

Rather, the unobservable differences between men and women hold a larger stake in the pay gap. Particularly at the top-side of the earnings distribution. So, a case for gender quotas is strong. Quotas could help to overcome prejudices – deliberate and unconscious. But quotas may do more harm than good. Because unwanted side-eye glances and scoffs are inevitable.

One action we can take toward eliminating the gender pay gap is to reconsider how “women’s work” is valued.

Solution: Revaluation of “women’s work”

“A woman’s worth”

The gender pay gap is maintained by a trifecta of: women’s employment status, women’s occupational choices and the valuation of “women’s work” (among other things). Introducing paternal leave addresses the first issue. Changing how boys and girls perceive certain occupations addresses the second. But we still need to tackle the last issue. And it’s an issue of pay equity. The good news is recent developments tell us we’re on the right track.

The gender pay gap is maintained by a trifecta of: women’s employment status, women’s occupational choices and the valuation of “women’s work” (among other things). Introducing paternal leave addresses the first issue. Changing how boys and girls perceive certain occupations addresses the second. But we still need to tackle the last issue. And it’s an issue of pay equity. The good news is recent developments tell us we’re on the right track.

“Women’s work” has historically been viewed as low skilled and of low value. Care work, specifically, generally commands less pay. But through the efforts of 2018 Kiwibank New Zealander of the Year, Kristine Bartlett and countless others, we’ve made a full 180° turn. The Employment Court held that care and support workers were underpaid precisely because the work is mainly performed by women. A $2.048 billion settlement was then legislated under the Care and Support Worker (Pay Equity) Act. And 55,000 care workers are set to receive a pay rise of between 15% and 50%.

Not only does a revaluation of “women’s work” help to narrow the earnings gap, but it may also provide an incentive for men to consider occupations traditionally held by women.

The more you earn, the less you keep

Income tax is not the only payment made on each dollar earned. There are other ways one’s pocket can feel lighter on pay day. Families receiving government support such as Working for Families (WFF) are most affected. Because WFF payments are not universal, but taper out as household income rises above a threshold ($42,700 p.a.). So, the one to really worry about is the effective marginal tax rate (EMTR).

Consider the following scenario: A sole parent receives a pay rise that pushes them into the 30% income tax bracket. However, they might prefer a pat on the back over the new paycheck. Because after income tax (30%) and ACC levies (1.21%) are paid, WFF payments abated (25%), student loan repayments made (12%), and Kiwisaver contributions withdrawn (3%), the parent could lose more than 70% (EMTR) of their new earnings.

For a two-parent household, the prospect of a high EMTR is particularly limiting for the secondary earner. For reasons including childcare and occupation, the secondary earner has traditionally been women. Compared to men, female labour supply is relatively more elastic – more flexible to meet the demands of the home.

The previous solutions look to further raise women’s economic involvement. But without addressing the nightmare combination of welfare and tax, the status quo is maintained. More work needs to be done to incentivise women, and enable them to keep more of their hard-earned wages on pay day.

Solution: Overhaul of the tax system

If it’s broke, fix it

To provide incentive for the secondary earner (women) to add more money to the jar, the abatement rate could be lowered. However, women’s experience with the tax system, as the secondary earners, may justify a complete overhaul. There’s merit in reviving the low flat-tax broad-based system of the 1980s. But this time, accompanied by a more considered user-pays scheme. The 90s tried this by aggregating all social assistance and applying a single abatement rate. But it failed terribly. And we’re still feeling the effects. Maybe it’s our turn to get it right.

Keeping the momentum going

Women’s economic status in New Zealand has improved since the days of the Hippie. Bell-bottoms, disco balls and Chuck Norris are out. But there are some trends from the 70s that we just can’t seem to shake. And it’s slowing progress. We’ve outlined a number of ways we can keep the momentum going.

Women’s economic status in New Zealand has improved since the days of the Hippie. Bell-bottoms, disco balls and Chuck Norris are out. But there are some trends from the 70s that we just can’t seem to shake. And it’s slowing progress. We’ve outlined a number of ways we can keep the momentum going.

But it is not lost on me that there is a cost to each of the ‘solutions’: careers day events and scholarships require funding; extending paternity leave cost the Finnish government a tidy sum; establishing workplace childcare may eat into company profits; a re-valuation of “women’s work” won’t be cheap; and a re-structure of the current tax transfer interface will likely cause a few headaches. But does the need to ensure women are participating in the economy as much as they desire, justify the expense? Of course. It’s time to clean out the closet.