- The Government delivered on its election promises in Budget 2024, with tax cuts presented as campaigned. But can they keep to their word and new projections? They’re walking a fine line.

- Treasury’s forecasts have softened yet again. High interest rates, still-high inflation, weakening demand and falls in productivity are dragging the Kiwi economy.

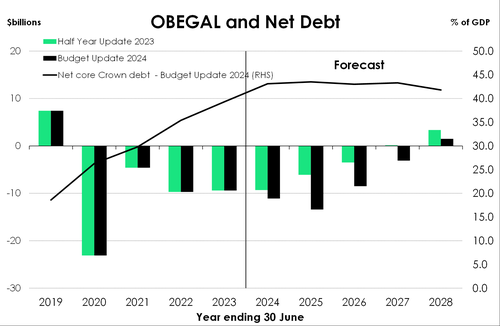

- A weaker economic outlook means a weaker fiscal outlook. No surprises. The Government’s books are in a worse state as revenue growth underperforms. And that’s despite a reduction in operating allowances. Deeper operating deficits in the near-term and a return to surplus – only just.

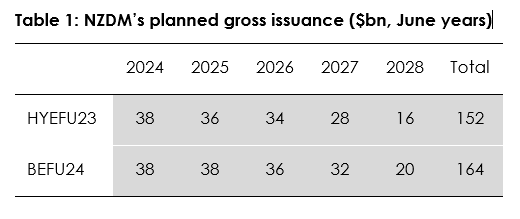

- Government’s debt pile continues to grow in the near-term. The peak remains at 43.5%, but is reached a year later in the 2028 fiscal year. More debt means more issuance - $12bn more over the next four years to be precise.

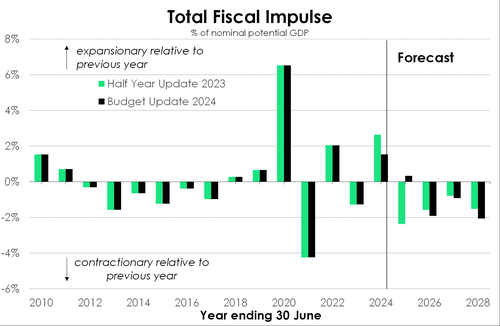

- For the RBNZ, Treasury’s updated fiscal impulse is key. And it appears fiscal consolidation too has been delayed. Fiscal settings are less tight than assumed in December. That doesn’t help the RBNZ’s quest in tackling the inflation beast.

Budget 2024 delivers on election promises, just. Fiscal neutrality was a key consideration, as revenue projections suffer from a bleaker reality.

Finance Minister, Nicola Willis, must feel like she's standing on quicksand. The economy is smaller than expected, and the outlook received a downgrade. That means the actual tax take, and the forecast tax take, keep sinking.

The numbers are softer across the board. Treasury expect lower growth, weaker productivity, and more debt. Economic growth starts to lift, off a lower base, into 2025, but hardly shoot the lights out beyond. The operating surplus is achieved, on paper, in 2028 - at the very end of the projections. The weaker reality means more debt. The debt management office will have to issue an additional $12bn beyond 2025 and out to 2028. Net debt rises to 43.5% and remains above previous projections.

It’s a difficult budget for any Government to deliver. We've been through a recession, so the temptation is to expand and spend. But inflation remains too high and the RBNZ is on the war path with restrictive interest rates. So, delivering a fiscally expansive budget would have fuelled inflation and poked the RBNZ bear.

The Government did a good job on delivering what was expected, and not much more. The promised tax cuts were delivered, as said, and appear to be fiscally neutral. That means they gave (tax cuts) with one hand, and took (spending cuts and some other tax hikes) with the other hand.

In terms of headline-grabbing announcements, the Government’s tax relief package was front and centre. From 31 July this year, New Zealand will be ushering in a new set of personal income tax thresholds. Alongside income tax, the Government increased the Working for Families in-work tax credit, and the income cap for the Independent Earner Tax Credit will increase. As announced at the mini-Budget, the Government’s tax relief package also extends to property investors. The Government has restored interest deductibility for residential rental property (full restoration from April 2025), and reduced the Brightline test for rental properties to two years from 10 years (effective from 1 July 2024). All up, the Government’s tax package will cost $3.7bn. But savings and other revenue initiatives are covering the bill, rather than additional borrowing.

As earlier signalled, Budget 2024 provides a top up to the multi-year capital allowance (MYCA) by $7bn. There’s now $7.5bn in the jar to fund future investment projects. Key investments as outlaid in the budget build on the existing capital pipeline. A couple to note is the $1.2bn set aside for the Regional Infrastructure Fund with an $200mn initial investment in to flood resilience infrastructure. And revamping our roads, rail and public transport received an almost $3bn cheque.

A $8.15bn was directed to health over the next four years, albeit mainly to cover cost pressures. And $3bn goes toward education largely for the creation of new schools and classrooms.

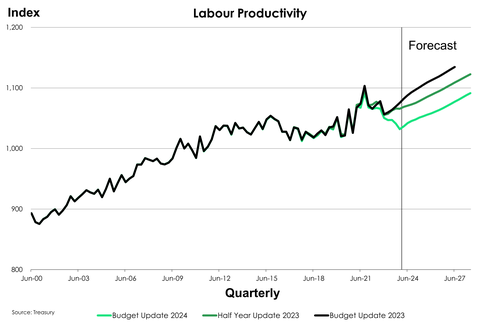

A lack of productivity drags the economy.

By no surprise, today we saw Treasury soften their outlook for the Kiwi economy. In previous updates, Treasury has had the tendency to view the economy with more optimism than most forecasters, including ourselves. Importantly previous Treasury forecasts have failed to foresee the two recessions we have recorded over the past five quarters.

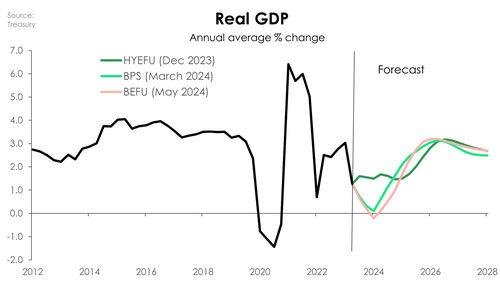

Now, given another much weaker starting point, Treasury have gone back to the drawing board and revised their forecasts for the Kiwi economy. Compared to their previous forecasts, Treasury now expects the economy to shrink by 0.2% in the year to June 2024. A significant fall from the expected 1.5% lift in their HYEFU in December 2023, and a later 0.1% expected in their budget policy statement released in March this year. But the worst is nearly over. Beyond 2024, we start to see the economy grow again. But it is at a slower rate than previously expected. In the year to June 2025 the economy is expected to grow 1.7%. Though that’s down from the expected 2.1% laid out in their March Budget Policy Statement. Thereafter, Treasury expect growth to average 2.9% over the final 3 years of the forecast period as interest rates continue to ease and the ‘tax package supports private sector incomes and demand’. However, with trend GDP expected to be 2% smaller than previously expected by the end of the forecast period, the consequences of lower output will carry through onto lower forecasts for tax revenue.

Now, given another much weaker starting point, Treasury have gone back to the drawing board and revised their forecasts for the Kiwi economy. Compared to their previous forecasts, Treasury now expects the economy to shrink by 0.2% in the year to June 2024. A significant fall from the expected 1.5% lift in their HYEFU in December 2023, and a later 0.1% expected in their budget policy statement released in March this year. But the worst is nearly over. Beyond 2024, we start to see the economy grow again. But it is at a slower rate than previously expected. In the year to June 2025 the economy is expected to grow 1.7%. Though that’s down from the expected 2.1% laid out in their March Budget Policy Statement. Thereafter, Treasury expect growth to average 2.9% over the final 3 years of the forecast period as interest rates continue to ease and the ‘tax package supports private sector incomes and demand’. However, with trend GDP expected to be 2% smaller than previously expected by the end of the forecast period, the consequences of lower output will carry through onto lower forecasts for tax revenue.

Rightly so, Treasury made the point to attribute the soft economic environment to a mixture of high interest rates, still high inflation, and weak domestic and global demand. But in the same tune to recent messaging from the RBNZ, the softer outlook to the Kiwi economy comes from lower estimates to Kiwi productivity. Primarily, lower estimates of labour productivity. Consistent with slowing global productivity growth, New Zealand has seen slowing productivity growth of just 0.2 per annum over the past 10 years – compared to the 1.4% per annum rate over the prior 20 years. And GDP per hour worked has now fallen more than 3% since September 2022. Whether it’s from lower productivity benefits from innovation, weak investment relative to employment growth or a slowdown in international trade and connections, we are simply not producing more output with our given inputs.

Rightly so, Treasury made the point to attribute the soft economic environment to a mixture of high interest rates, still high inflation, and weak domestic and global demand. But in the same tune to recent messaging from the RBNZ, the softer outlook to the Kiwi economy comes from lower estimates to Kiwi productivity. Primarily, lower estimates of labour productivity. Consistent with slowing global productivity growth, New Zealand has seen slowing productivity growth of just 0.2 per annum over the past 10 years – compared to the 1.4% per annum rate over the prior 20 years. And GDP per hour worked has now fallen more than 3% since September 2022. Whether it’s from lower productivity benefits from innovation, weak investment relative to employment growth or a slowdown in international trade and connections, we are simply not producing more output with our given inputs.

Beyond the size and productivity of the economy, changes to Treasury’s forecasts were more marginal. Lower estimates to economic output and high migration saw Treasury revise up their forecast for unemployment which now peaks at 5.3% by the end of 2024 compared to the previous peak of 5.2%.

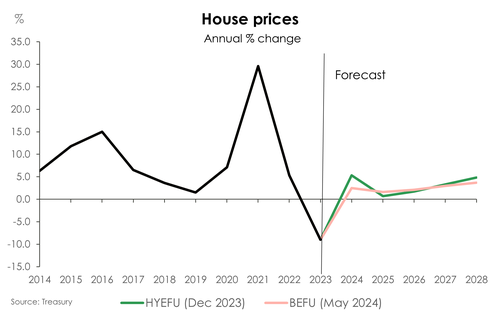

Meanwhile in line with a weaker economy and higher unemployment Treasury’s forecast for inflation and interest saw slight revisions. Much like us, Treasury still expects inflation to fall below 3% in the September quarter of 2024, just with a little more  strength in the near term. But they are now envisioning a faster return to the 2% midpoint a whole year earlier in June 2026 rather than June 2027. And following a slightly lower inflation outlook, Treasury has also lowered their forecast for the 90-day interest rate track with easing in wholesale interest rates sooner and by more than previously expected. Come next year, Treasury’s 90day Track now sees interest rates falling below 5% in the first quarter of 2025, a quarter earlier than before. Yet despite lower rates, the sluggish activity in the housing market has seen Treasury lower their house price forecast with gains of just 2.5% (down from 5.3%) to be made in the year to June. For now, high interests continue to weigh heavily on the housing market.

strength in the near term. But they are now envisioning a faster return to the 2% midpoint a whole year earlier in June 2026 rather than June 2027. And following a slightly lower inflation outlook, Treasury has also lowered their forecast for the 90-day interest rate track with easing in wholesale interest rates sooner and by more than previously expected. Come next year, Treasury’s 90day Track now sees interest rates falling below 5% in the first quarter of 2025, a quarter earlier than before. Yet despite lower rates, the sluggish activity in the housing market has seen Treasury lower their house price forecast with gains of just 2.5% (down from 5.3%) to be made in the year to June. For now, high interests continue to weigh heavily on the housing market.

Deeper deficits and little wriggle room.

As forewarned, the Treasury’s fiscal outlook has been materially downgraded. For one, the starting point is much weaker than assumed in December. The nominal economy is much smaller than previously thought, and thus, so too is the tax base. Smaller operating allowances that the Government has set going forward provides some offset. However, the Government’s books have clearly deteriorated.

Core Crown revenues continue to undershoot forecasts. The corporate tax take, in particular, is falling short of forecasts. It’s a clear reflection of slowing economic activity. The rising interest rate environment is taking a toll on the economy, and demand is easing. These drivers are expected to persist, largely resulting in a downgrade to expected nominal GDP in each year of the forecast period. Alongside the personal income tax cuts, a whopping $28.3bn has been taken out of the core Crown tax revenue projections over the next five years (excluding the impact of the tax policy changes, the tax revenue track has been lowered $18.5bn).

The reduction in the Government’s operating allowance provides some offset to the weaker outlook for core Crown tax revenue – but not a lot. On the other side of the ledger, the expenditure track was also lowered. Core Crown expenses are expected to be smaller in each year compared to the HYEFU. The operating allowance for Budget 2024 was pared back to $3.2bn from the $3.5bn earmarked by the previous Government. The operating allowance for future budgets were also reduced to $2.3bn. That doesn’t give the Government much wriggle room. It will no doubt be difficult for the Government to colour within the lines.

Piecing it altogether, the Government is expected to run deeper operating deficits in the near-term – despite a smaller operating allowance. The operating (OBEGAL) deficit grows in the near-term, reaching a low of $13.4bn – greater than the $9.3bn deficit at the HYEFU. Thereafter, the operating deficits begin to improve as the economy bounces back and growth in taxable profits improves. At the same time, the expenses are projected to grow at a slowing pace. Nonetheless, the return of the operating balance to surplus was pushed out by a year – once again – to 2027/28, the end of the forecast period. And at $1.5bn, it is just 0.3% of GDP, and much smaller than the $3.4bn HYEFU projection.

Piecing it altogether, the Government is expected to run deeper operating deficits in the near-term – despite a smaller operating allowance. The operating (OBEGAL) deficit grows in the near-term, reaching a low of $13.4bn – greater than the $9.3bn deficit at the HYEFU. Thereafter, the operating deficits begin to improve as the economy bounces back and growth in taxable profits improves. At the same time, the expenses are projected to grow at a slowing pace. Nonetheless, the return of the operating balance to surplus was pushed out by a year – once again – to 2027/28, the end of the forecast period. And at $1.5bn, it is just 0.3% of GDP, and much smaller than the $3.4bn HYEFU projection.

The Budget Policy Statement delivered in March made tweaks to debt settings and definitions. The Government is winding back the clock to adopt the 2009 definition of net core Crown debt. Investment assets held by the NZ Super Fund, among other things, will now be excluded from the debt measure. Deeper deficits in the near-term has pushed out the eventual peak in debt load. As a share of the economy, net debt is still expected to peak at 43.5%, but a year later in the 2025 fiscal year. Net debt declines thereafter, remains above 40% by the end of the forecast period – not quite meeting the Government’s 20-40% long-term goal.

Not what the RBNZ wants to see.

Treasury’s fiscal impulse analysis provides a measure of how much fiscal policy is either adding to or taking away from aggregate demand from one year to the next. Over the forecast period, fiscal settings are assessed to be contractionary. However, the yearly profile has changed. And in a way that the RBNZ may not be happy with. In 2024/25 fiscal settings have increased from moved to contractionary territory to more neutral-slightly expansionary. Fiscal consolidation begins a year later, and is slightly smaller, than expected in the HYEFU. That won’t please the RBNZ, and makes their quest of tackling inflation that much harder.

Treasury’s fiscal impulse analysis provides a measure of how much fiscal policy is either adding to or taking away from aggregate demand from one year to the next. Over the forecast period, fiscal settings are assessed to be contractionary. However, the yearly profile has changed. And in a way that the RBNZ may not be happy with. In 2024/25 fiscal settings have increased from moved to contractionary territory to more neutral-slightly expansionary. Fiscal consolidation begins a year later, and is slightly smaller, than expected in the HYEFU. That won’t please the RBNZ, and makes their quest of tackling inflation that much harder.

More debt, more issuance.

Deeper operating deficits, a smaller forecast tax base, and a top up to capital investment allowance mean a lift in the debt profile. And more debt needed means more issuance. Planned gross issuance was increased – once again – by $12bn out to the 2027 fiscal year, within the ballpark of estimates ahead of the announcement. The planned issuance profile is below.