Key points:- Net migration in New Zealand has surged to a record high of 72,000 people over the past year.

- Net migration is being driven by the combination of fewer Kiwis heading overseas, more returning home, and an increase in new arrivals. We expect migration numbers to remain elevated for some time yet.

- A rapidly expanding population is boosting both supply and demand in the economy. The composition of migration matters for the net impact on NZ.

- With a growing population come challenges to ensure that we have the right combination of skills and resources to help NZ thrive.

Summary

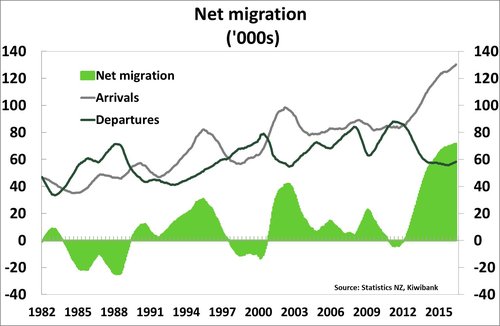

Net migration has continued to hit new record highs in 2017, far surpassing the last migration boom we experienced back in the mid-2000’s. New Zealand has seen a net gain of 72,000 people due to migration over the past year and current trends suggest that these elevated numbers are unlikely to turn around anytime soon. The rapid rise in net migration in recent years has meant that New Zealand is currently experiencing the fastest pace of population growth seen since the mid-1970s. A rapidly growing population has an impact on the NZ economy through increased demand for goods and services, higher demand for housing and also a larger supply of available workers.

A relatively buoyant NZ labour market has continued to attract foreign workers at the same time as many other countries are tightening their borders and geopolitical tensions are rising - adding to the appeal of NZ as a place to emigrate to. At the same time, these factors are also encouraging more New Zealanders to stay at home and an increasing number to come back from overseas.

Heading into this year’s general election, the optimal settings for net migration remain a hot topic, with most major political parties looking to reduce migration numbers. Absent any major changes in government policy, we expect net migration to remain elevated at around 70,000+ until the end of 2017 and then to gradually ease over the next few years.

Strong population growth has been a contributing factor to NZ’s solid economic growth in recent years – with more people in the country increasing overall demand for goods and services as well as housing. In this note we take a look at some of the key drivers of migration, who is coming into the country and what some of the major economic impacts have been from rapid migration-led population growth.

Well that escalated quickly

Last time we wrote a special piece on net migration (back in 2014) we thought then that we were in the midst of a significant migration boom, with a net gain of 34,000. Since then, we have in fact seen the pace of annual net migration more than double to 72,000. It’s important to note here that we are talking about net migration, not just inward arrivals numbers (often referred to as immigration). Net migration is made up of fewer people choosing to leave New Zealand (lower departures) as well as inward arrivals (see chart below). Net migration turned positive in New Zealand at the start of 2013 and has been rapidly climbing ever since, driven by both an increase in inward migration as well as fewer people departing.

Last time we wrote a special piece on net migration (back in 2014) we thought then that we were in the midst of a significant migration boom, with a net gain of 34,000. Since then, we have in fact seen the pace of annual net migration more than double to 72,000. It’s important to note here that we are talking about net migration, not just inward arrivals numbers (often referred to as immigration). Net migration is made up of fewer people choosing to leave New Zealand (lower departures) as well as inward arrivals (see chart below). Net migration turned positive in New Zealand at the start of 2013 and has been rapidly climbing ever since, driven by both an increase in inward migration as well as fewer people departing.

In the past year, departures have fallen to the lowest level since the early 2000’s, with more New Zealanders staying put in response to attractive employment opportunities locally, and a changing political environment globally.

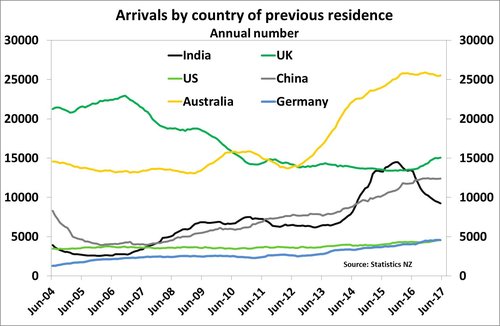

On the arrivals side we have seen a sharp pick-up in the number of arrivals into NZ since 2012, with the biggest inflow of migrant arrivals in recent years coming from Australia. After our neighbours across the ditch, our next biggest source of arrivals has been from the UK. After trending lower for many years, arrivals numbers from the UK started to pick up again in 2015 and have been steadily rising since. Indicators suggest that this trend is set to continue in the wake of the Brexit vote, driven by a combination of more New Zealanders returning home as it becomes more difficult to stay in the UK (and the labour market softens) and an increasing number of Brits looking at moving to the other side of the world.

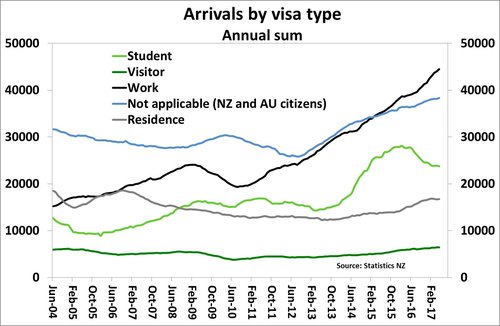

Our third biggest source of arrivals has historically alternated between China and India. Arrivals from India have been particularly volatile over the last five years due to various changes in international student rules. Almost 70% of arrivals from India in the past two years have arrived on student visas. Indian arrival numbers picked up dramatically in 2013 – corresponding to the timing of rule changes to allow education providers to assume responsibility for English language testing requirements. This rule change was then reversed in late 2015 and we have seen a subsequent turn around in Indian student visa numbers from an annual rate of 10,000/year at the end of 2015, down to around 6,500/year currently. Arrivals from China on the other hand have continued to rise, with a relatively smaller share arriving on student visas (about 45% over the past two years) and a larger number on work or residence visas.

Brain drain no longer

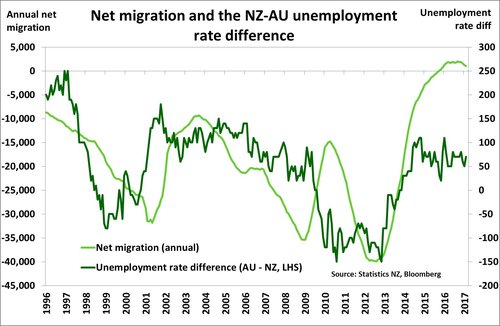

The old tradition of New Zealanders heading overseas in search of better opportunities has halted in recent years. One of the clear trends in migration has been the turnaround in net migration between NZ and Australia (see chart below) and we are now seeing a net gain in people from Australia, compared to the past 20 years of net population outflows. The numbers of New Zealanders choosing to relocate across the Tasman is at the lowest levels seen since 2003. At the same time many more New Zealanders are returning from overseas and there are also an increasing number of Australians arriving on our shores. As can be seen in the chart above, net migration between the two economies generally follows the attractiveness of the two labour markets, although migration gains have run even further ahead of relative labour market conditions in recent years.

The old tradition of New Zealanders heading overseas in search of better opportunities has halted in recent years. One of the clear trends in migration has been the turnaround in net migration between NZ and Australia (see chart below) and we are now seeing a net gain in people from Australia, compared to the past 20 years of net population outflows. The numbers of New Zealanders choosing to relocate across the Tasman is at the lowest levels seen since 2003. At the same time many more New Zealanders are returning from overseas and there are also an increasing number of Australians arriving on our shores. As can be seen in the chart above, net migration between the two economies generally follows the attractiveness of the two labour markets, although migration gains have run even further ahead of relative labour market conditions in recent years.

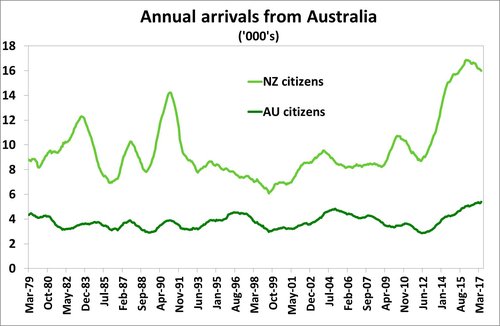

Migration between Australia and New Zealand is driven by a range of factors but one of the big ones has been relative job opportunities. The slowdown in mining investment in Australia has seen fewer kiwis heading across the ditch in search of lucrative mining-industry jobs and an increasing number now returning home (see chart below). In addition, the Australian government has scrapped benefit entitlements and tightened up permanent residency requirements for New Zealanders living in Australia. Kiwis departing to Australia numbered just under 24,000 over the year to July – well down from an annual total of 54,000 in mid-2012. At the same time, the number of NZ citizens moving back from Australia has increased rapidly over the past few years. It appears that arrivals from Australia may now be showing some early signs of pulling back from elevated levels. However, with employment opportunities in NZ expected to remain stronger than those in Australia over the year ahead, we don’t expect to see a major reversal in these numbers anytime soon.

Migration between Australia and New Zealand is driven by a range of factors but one of the big ones has been relative job opportunities. The slowdown in mining investment in Australia has seen fewer kiwis heading across the ditch in search of lucrative mining-industry jobs and an increasing number now returning home (see chart below). In addition, the Australian government has scrapped benefit entitlements and tightened up permanent residency requirements for New Zealanders living in Australia. Kiwis departing to Australia numbered just under 24,000 over the year to July – well down from an annual total of 54,000 in mid-2012. At the same time, the number of NZ citizens moving back from Australia has increased rapidly over the past few years. It appears that arrivals from Australia may now be showing some early signs of pulling back from elevated levels. However, with employment opportunities in NZ expected to remain stronger than those in Australia over the year ahead, we don’t expect to see a major reversal in these numbers anytime soon.

In addition, departures to the UK have also dropped off significantly following the global financial crisis and more recently, the Brexit vote. In the late 90’s/early 2000’s about 15,000-16,000 people left NZ every year to move to the UK. In the year to March 2017, that number totaled about 8,500.

Where are all these people living?

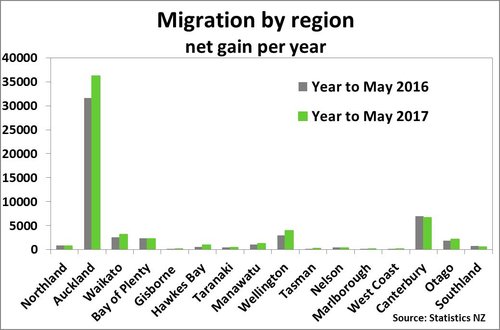

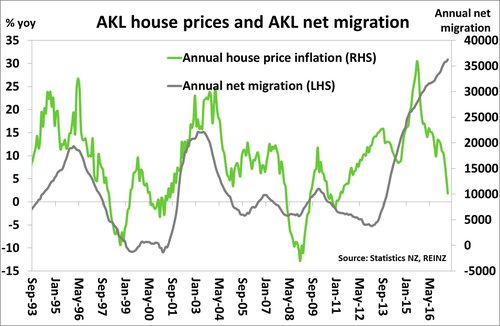

As noted above, Auckland has seen outsized population gains from net migration relative to the rest of the country. Data suggests that almost half the gain in net migration has been concentrated in Auckland, despite Auckland only accounting for about 35% of NZ’s total population. This has been driven by arrivals, with over 45% of those arriving in NZ saying they expected to make Auckland their home town (although it is hard to tell if people always end up locating themselves in Auckland as intended). Over the year to June 2016, Auckland’s population grew at a pace of 2.8% yoy, with about 70% of that increase due to net migration.

As noted above, Auckland has seen outsized population gains from net migration relative to the rest of the country. Data suggests that almost half the gain in net migration has been concentrated in Auckland, despite Auckland only accounting for about 35% of NZ’s total population. This has been driven by arrivals, with over 45% of those arriving in NZ saying they expected to make Auckland their home town (although it is hard to tell if people always end up locating themselves in Auckland as intended). Over the year to June 2016, Auckland’s population grew at a pace of 2.8% yoy, with about 70% of that increase due to net migration.

The other major region that has experienced solid net migration has been Canterbury as the region continues to rebuild itself following the 2011 earthquake.

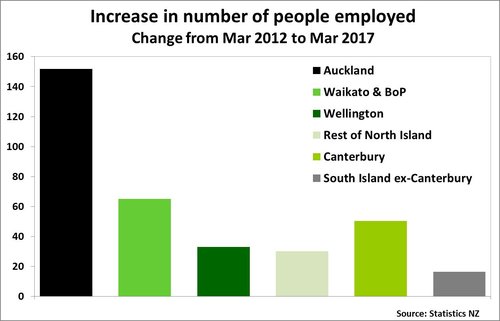

In the last five years, Canterbury has seen its population grow by 26,500 due to net migration. Government policies are now aiming to try and distribute new migrants across the regions now to reduce the pressure that a growing population is putting on resources in Auckland. However, this also relies on jobs in those regions for new migrants to move into. Auckland has traditionally been the region that has experienced the strongest population growth, although we are also now seeing a significant increase in employment in upper North Island areas such as the Waikato and Bay of Plenty.

This time is different

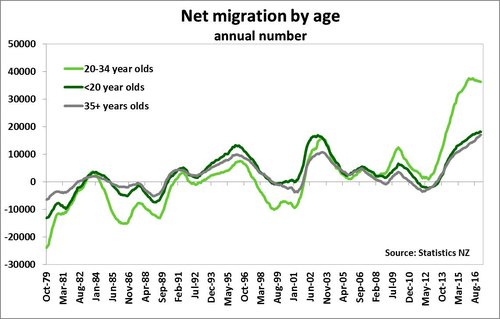

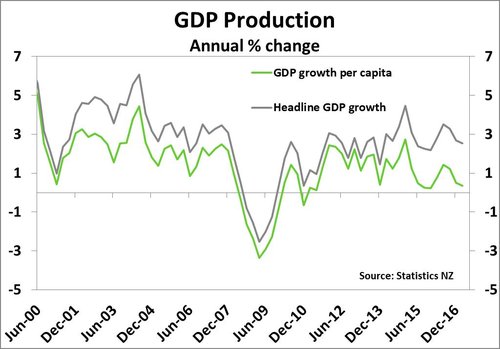

Last time we had a net migration boom back in the early-mid 2000’s, the economic impacts included strong GDP growth due to higher demand, rising inflation, increasing house prices and residential investment. Interest rates increased significantly in order to rein in rising inflation and a booming credit cycle. Despite the fact that net migration is more than double than pace seen in the 2000’s, this net migration boom has had a much more muted impact on growth and inflation. This is in part due to the different composition of migrants we have seen this time around.

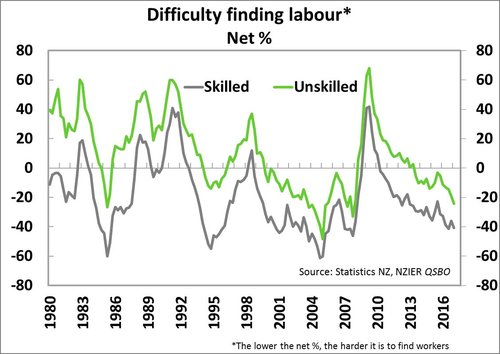

While in the previous cycle population gains were relatively evenly spread across age groups, this time there has been a clear concentration in those aged between 20-35 years old. Over the past year, almost exactly half of the gain in net migrants was concentrated in that age group, with the rest equally divided between those less than 20 and those over 35 years old. This concentration of a younger cohort has helped boost NZ’s workforce at a time when demand has been strong and firms are reporting skilled worker shortages. This has helped support economic growth at a time when New Zealand’s native workforce is naturally ageing with the baby boomers starting to retire.

Positive net migration numbers boost both demand and supply sides of the economy but in the past they have caused a much more significant increase in the demand for goods and services than they have helped to boost supply. This typically leads to rising pressure on existing resources, causing higher inflation as demand for goods and services exceeds supply. This time around however, due to the concentration of migration in younger age groups, there has been a much larger supply response from those additional people entering the workforce – lifting workforce participation in NZ to a record high. In the last migration cycle there tended to be an increasing number of families, e.g. a family of four (two adults, two kids), with only one or two of those four people entering the workforce and therefore helping to boost supply, but four people demanding goods and services. This time around, migration numbers appear to be concentrated in singles or couples without children who in many cases are both entering the workforce – therefore we are getting an almost one-for-one increase in both supply and demand. Even international students studying here end up working in many cases (with most student visas allowing up to 20 hours of work per week). This is providing NZ with a helpful boost to our younger workforce which will hopefully offset some of the negative fiscal impact from an ageing local population.

Positive net migration numbers boost both demand and supply sides of the economy but in the past they have caused a much more significant increase in the demand for goods and services than they have helped to boost supply. This typically leads to rising pressure on existing resources, causing higher inflation as demand for goods and services exceeds supply. This time around however, due to the concentration of migration in younger age groups, there has been a much larger supply response from those additional people entering the workforce – lifting workforce participation in NZ to a record high. In the last migration cycle there tended to be an increasing number of families, e.g. a family of four (two adults, two kids), with only one or two of those four people entering the workforce and therefore helping to boost supply, but four people demanding goods and services. This time around, migration numbers appear to be concentrated in singles or couples without children who in many cases are both entering the workforce – therefore we are getting an almost one-for-one increase in both supply and demand. Even international students studying here end up working in many cases (with most student visas allowing up to 20 hours of work per week). This is providing NZ with a helpful boost to our younger workforce which will hopefully offset some of the negative fiscal impact from an ageing local population.

This migration cycle has caused both the supply and demand sides of the economy to increase, generating less inflation pressure than we have seen in previous migration booms. Whether this more muted impact on growth continues will depend on any changes in the composition of migration over the next couple of years – either naturally or through government policy.

Is it getting crowded in here?

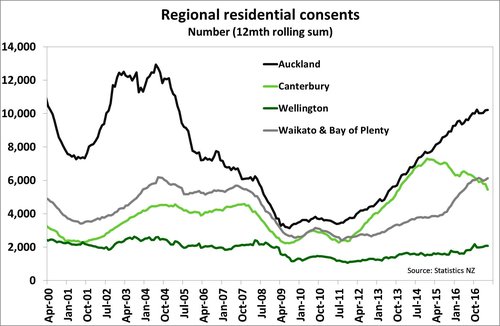

With arrivals numbers at a record high and departures at a low level, the country is inevitably becoming busier – particularly in Auckland. However, ‘crowded’ in NZ is very much a relative term given the size of the country’s population compared with its land mass. On a per capita basis, NZ remains very sparsely populated, with an average of 17 people per square kilometre – compared with the OECD average of around 33 people/sq km . While in theory this means we have plenty of room to expand, more and more people are choosing to locate themselves in Auckland and its surrounds. In addition, population projections from Statistics NZ , estimate that more than half of New Zealand’s population growth over the next 35 years will be concentrated in Auckland. Auckland’s population is projected to total 2.3mn by 2043 (from just under 1.5mn currently), this would mean close to an additional 270,000 homes need to be built between now and then just to keep up with that growth rate. That equates to needing to build about 10,300 per year, whereas on average in the last ten years we have consented around 6000 dwellings per year in Auckland – with probably only 5000-5500 of those getting built. While the number of residential consents has improved in recent years, we have never returned to the pace of building in Auckland that we saw during the last housing and net migration boom through the early/mid 2000’s (see chart below).

With arrivals numbers at a record high and departures at a low level, the country is inevitably becoming busier – particularly in Auckland. However, ‘crowded’ in NZ is very much a relative term given the size of the country’s population compared with its land mass. On a per capita basis, NZ remains very sparsely populated, with an average of 17 people per square kilometre – compared with the OECD average of around 33 people/sq km . While in theory this means we have plenty of room to expand, more and more people are choosing to locate themselves in Auckland and its surrounds. In addition, population projections from Statistics NZ , estimate that more than half of New Zealand’s population growth over the next 35 years will be concentrated in Auckland. Auckland’s population is projected to total 2.3mn by 2043 (from just under 1.5mn currently), this would mean close to an additional 270,000 homes need to be built between now and then just to keep up with that growth rate. That equates to needing to build about 10,300 per year, whereas on average in the last ten years we have consented around 6000 dwellings per year in Auckland – with probably only 5000-5500 of those getting built. While the number of residential consents has improved in recent years, we have never returned to the pace of building in Auckland that we saw during the last housing and net migration boom through the early/mid 2000’s (see chart below).

With Auckland experiencing the strongest population gains from net migration, it is unsurprising that this has put pressure on the Auckland housing market. The fundamental economics of under-building relative to population growth can be seen in the sharp increase in house prices in Auckland in recent years. While the Auckland housing market has cooled rapidly in recent months (due to a combination of tighter credit conditions, LVR rule changes, slowly rising interest rates, affordability constraints, uncertainty around the upcoming general election, and questions over the sustainability of further capital gains), in our view there remains a fundamental imbalance between population growth and supply of housing that could see a rebound in activity and prices toward the end of this year.

With Auckland experiencing the strongest population gains from net migration, it is unsurprising that this has put pressure on the Auckland housing market. The fundamental economics of under-building relative to population growth can be seen in the sharp increase in house prices in Auckland in recent years. While the Auckland housing market has cooled rapidly in recent months (due to a combination of tighter credit conditions, LVR rule changes, slowly rising interest rates, affordability constraints, uncertainty around the upcoming general election, and questions over the sustainability of further capital gains), in our view there remains a fundamental imbalance between population growth and supply of housing that could see a rebound in activity and prices toward the end of this year.

While more people in the country will put additional pressure on an already stretched housing market, there are positive benefits to the economy from migration. A growing population adds more demand into the economy which benefits local businesses and creates more employment opportunities. In addition, research from the NZ Initiative shows that on average migrants pay significantly more tax than local New Zealanders . This is in part due to the age structure of the local population, with an aging population and baby boomers retiring, the fact that net migration has been concentrated in younger age groups is helping boost the tax take. This could help stave off some of the negative impacts from NZ’s aging population for a little longer.

While more people in the country will put additional pressure on an already stretched housing market, there are positive benefits to the economy from migration. A growing population adds more demand into the economy which benefits local businesses and creates more employment opportunities. In addition, research from the NZ Initiative shows that on average migrants pay significantly more tax than local New Zealanders . This is in part due to the age structure of the local population, with an aging population and baby boomers retiring, the fact that net migration has been concentrated in younger age groups is helping boost the tax take. This could help stave off some of the negative impacts from NZ’s aging population for a little longer.

In the wake of the Canterbury earthquake, significant inward migration flows helped to meet the strong demand for construction workers. Many of these workers have now shifted to Auckland to help with numerous construction projects there, but firms are still reporting acute shortages of skilled construction workers and tradespeople. We are also seeing skill shortages increase in other sectors, with a net 47% of firms reporting that it is difficult to find skilled labour in NZ at the moment - and that is with the majority of arrivals into NZ are already coming in on work visas. Ensuring that we are getting migrants with the right skill levels to fill sectors with acute labour shortages would help ensure the economy can keep growing at a steady pace.

In the wake of the Canterbury earthquake, significant inward migration flows helped to meet the strong demand for construction workers. Many of these workers have now shifted to Auckland to help with numerous construction projects there, but firms are still reporting acute shortages of skilled construction workers and tradespeople. We are also seeing skill shortages increase in other sectors, with a net 47% of firms reporting that it is difficult to find skilled labour in NZ at the moment - and that is with the majority of arrivals into NZ are already coming in on work visas. Ensuring that we are getting migrants with the right skill levels to fill sectors with acute labour shortages would help ensure the economy can keep growing at a steady pace.

Conclusion

Net migration in NZ has now risen to levels that no policymaker (or economist) anticipated a few years ago. This boom in net migration has been driven by the combination of more New Zealanders choosing to stay put, and an increasing number of New Zealanders returning home as well as new migrants arriving into the country. It wasn’t so long ago that we were very concerned about an exodus of Kiwis offshore, so the fact that so many people now want to live in New Zealand is something we should be proud of - people are essentially voting with their feet and deciding that NZ as a desirable place to live. With a growing population we have seen both the supply and demand sides of the economy receive a boost. More people in the country mean increased demand for goods and services. However, housing and infrastructure investment haven’t kept pace with population growth which is now causing bottle necks.

Rising net migration also increases the capacity of the economy due to a larger labour force. This has been particularly evident in this migration cycle with gains concentrated in those aged 20-35 and the large number of arrivals on work visas. This means that as firms have expanded and employment growth has been strong, there has been a growing pool of workers – helping meet demand and increasing capacity in the economy. Even with workforce participation at a record high of 70.6%, the unemployment rate has declined to 4.9%.

The net effect of these demand/supply dynamics have been different in this migration cycle compared to that seen over the early-mid 2000’s, in large part due to population growth being concentrated in younger workers. Whereas the last migration cycle saw an outsized impact on demand, this time around both supply and demand have risen closely in step - causing less inflation pressure from population growth than would be expected.

The economy expanded at a pace of 2.5% over the year to March 2017, but GDP growth per capita has been more muted at 0.3% yoy. While there has always been a gap between headline GDP growth and per capita output (not everyone in the country will be actively contributing to production e.g. children and retirees), the gap has been widening in recent years – at the same time as net migration has been rising. This could in part be due to the fact that younger workers tend to be less productive as they are still picking up skills and are in training. In addition, students account for a fair share of net migration gains and the productive benefits from these people takes time to feed through the economy.

The economy expanded at a pace of 2.5% over the year to March 2017, but GDP growth per capita has been more muted at 0.3% yoy. While there has always been a gap between headline GDP growth and per capita output (not everyone in the country will be actively contributing to production e.g. children and retirees), the gap has been widening in recent years – at the same time as net migration has been rising. This could in part be due to the fact that younger workers tend to be less productive as they are still picking up skills and are in training. In addition, students account for a fair share of net migration gains and the productive benefits from these people takes time to feed through the economy.

In the near-term, the fundamentals supporting net migration are unlikely to change, namely; NZ’s solid economic performance, attractive job opportunities (particularly vis-à-vis Australia) and our isolation from the rising geo-political tensions and unrest we are seeing in other parts of the world. Over the medium-term we expect the pace of net migration to eventually slow as the outlook in other major economies improves - but that is likely to be a gradual process. In the mean-time, the upcoming general election could see migration policies tightened up. Party policies announced to-date range from tweaks to current settings (National) to restricting net migration to an annual rate of 10,000 (NZFirst). If we see wide-sweeping changes to migration policy then this would have a flow on effect across our economy – with the impact dependent on how aggressively migration numbers were reined in. A sharp reduction in net migration numbers could cause problems for employers given the acute skilled worker shortages currently reported; while net migration carrying on at current levels will require greater housing and infrastructure investment (particularly if the current pace continues for some time). Either way, we expect net migration to remain a key issue for both the RBNZ and politicians for years to come.