Key points:

- The New Zealand housing market has cooled convincingly over the past year.

- In our view, this slowdown has been caused by a confluence of factors including LVR restrictions, pre (and post) election uncertainty, affordability constraints and tighter credit conditions.

- However, there remains a gap between supply and demand that is unlikely to be corrected in the near-term.

- The outlook for the housing market over the year ahead remains uncertain. We still expect to see a small rebound in activity over the next six months, but price gains are likely to be much more limited.

The New Zealand housing market has undoubtedly cooled over the past year. House sales are 26% lower across the country compared with a year ago and house price appreciation has stalled to essentially flat over the last year. So is the housing boom turning to a bust or is this just a temporary bump in the road? In this note we take a look at some of the key drivers of NZ’s housing market and the implications for the outlook.

Why have things slowed down?

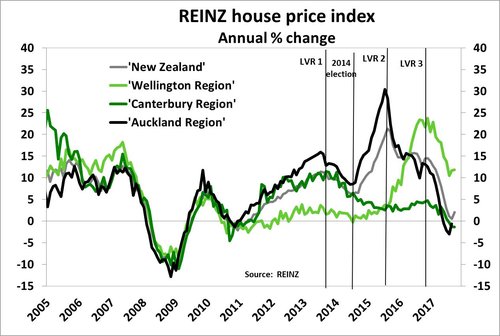

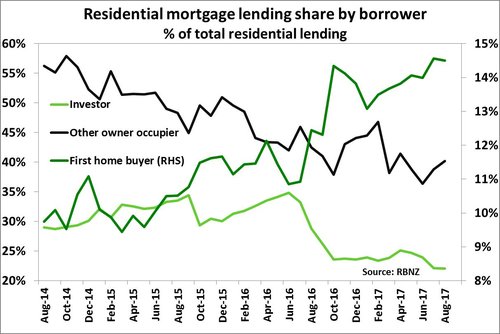

T here are many forces currently at play in the NZ housing market that we believe are driving the current slowdown. First of all, the RBNZ tightened loan-to-value ratio (LVR) restrictions for property investment toward the end of 2016 (see ‘LVR 3’ on chart above) which appears to have had a significant impact on property investment. The new rules require essentially a 40% deposit when buying a residential property that isn’t owner-occupied. For most owner-occupier purchases, a 20% deposit requirement has been in place since late 2013 (‘LVR 1’ on chart).

here are many forces currently at play in the NZ housing market that we believe are driving the current slowdown. First of all, the RBNZ tightened loan-to-value ratio (LVR) restrictions for property investment toward the end of 2016 (see ‘LVR 3’ on chart above) which appears to have had a significant impact on property investment. The new rules require essentially a 40% deposit when buying a residential property that isn’t owner-occupied. For most owner-occupier purchases, a 20% deposit requirement has been in place since late 2013 (‘LVR 1’ on chart).

Second, uncertainty ahead of the 2017 general election has seen a more cautious approach from property buyers – particularly the investor segment. This was especially evident when there was still significant talk of introducing a capital gains tax, but the general policy uncertainty also caused people to hold off major buying decisions – similar to the pattern we saw prior to the 2014 election. Labour has proposed increasing the bright-line test from two to five years – meaning that those who buy and sell an investment property within five years will have to pay tax on the capital gains over that time. In addition, Labour and NZ First both want to ban foreigners from purchasing NZ land and property. More significantly in our view, is the prospect of the new government scrapping the ability for investors to offset losses on their rental properties against income tax - which has been an attractive feature for many investors. Now that we have a new government, we are watching closely for the specifics around implementation of proposed housing policies. If implemented in full, these policies are likely to reduce demand from property investors further in the year ahead but on the flip-side may provide opportunities for more owner-occupiers/first-home buyers to get into the market.

Third, affordability constraints – particularly in Auckland where the median house price to income ratio is running at over 9x – means that saving a deposit and paying the mortgage are a higher hurdle for the average household. New Zealand’s overall price–to-income ratio is around 6x, but that masks a wide range of variability - from a ratio of 12.7x in Queenstown, down to a much more affordable 2.6x in Whanganui. Measures of affordability are now just starting to improve as house price growth has moderated and wholesale interest rates have shifted marginally lower in recent months. But rising mortgage rates in coming years could put additional pressure on affordability, particularly if house prices continue to rise – increasing the dollar value of debt taken on by the average buyer.

Finally, in response to a more restrictive funding environment, we have seen housing credit growth reined in over the last year. Mostly, these changes have been tweaks around the edges, but there is an increased degree of caution present around residential property-secured lending in the market at present. The growth in housing-related lending has pulled back from a cycle-peak of 9.1% yoy in August 2016, down to a pace of 6.9% yoy in August 2017. This is the slowest growth rate seen since late 2015, although it remains above the post-GFC average growth rate of around 5% yoy.

Underlying demand remains while supply lags behind

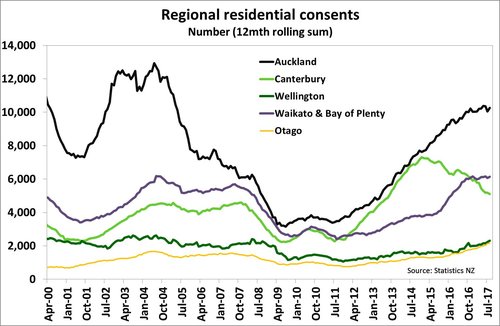

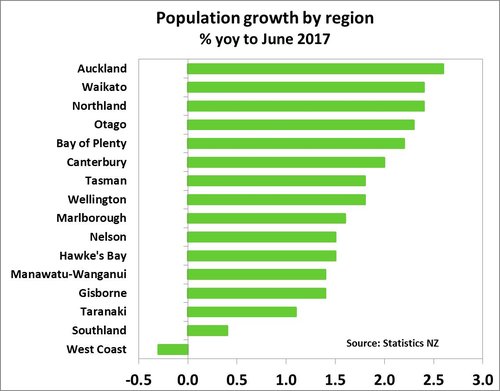

The latest figures from Statistics NZ show that New Zealand’s population increased by 2.1% over the year to June 2017. In Auckland the growth rate was higher at 2.6% yoy – or equivalent to an additional 42,700 people. Assuming an average of 2.7 people per household (the average household size measured in the 2013 consensus) implies that around 15,800 additional houses needed to have been built in Auckland over the past year to keep pace with population growth. In reality, just over 10,000 dwellings were consented with an estimated 7,000-8,000 of those actually getting completed. So in Auckland alone there was a shortfall in residential dwellings of about 8,000 houses last year. Additionally, new building consents have been lagging behind population growth in our largest city for quite some time. Estimates suggest that there is a pre-existing shortage of somewhere between 30,000-40,000 dwellings in Auckland.

The latest figures from Statistics NZ show that New Zealand’s population increased by 2.1% over the year to June 2017. In Auckland the growth rate was higher at 2.6% yoy – or equivalent to an additional 42,700 people. Assuming an average of 2.7 people per household (the average household size measured in the 2013 consensus) implies that around 15,800 additional houses needed to have been built in Auckland over the past year to keep pace with population growth. In reality, just over 10,000 dwellings were consented with an estimated 7,000-8,000 of those actually getting completed. So in Auckland alone there was a shortfall in residential dwellings of about 8,000 houses last year. Additionally, new building consents have been lagging behind population growth in our largest city for quite some time. Estimates suggest that there is a pre-existing shortage of somewhere between 30,000-40,000 dwellings in Auckland.

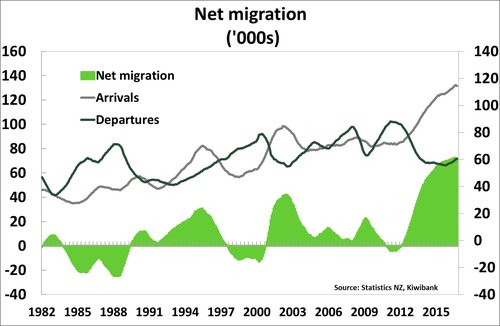

Across the rest of the country we have seen strong population growth in areas such as the upper North Island and Otago (see chart below), but almost every region has seen its population expand over the past year. The newly formed Labour-NZ First coalition government is looking to both increase the supply of housing and also cut net migration numbers – which theoretically should help bring supply and demand in the market back into balance. Population growth has in large part been driven by record-high net migration levels in the past few years. Net migration has contributed over 2/3rds of the increase in population – with the other 1/3rd due to natural population increase (more births than deaths). Under the new government, the Labour party’s policy of cutting net migration by 20,000-30,000 per year (from the current annual rate of 71,000) appears to be the preferred policy – rather than NZ First’s much more restrictive stance of cutting net migration to an annual rate of 10,000. The reduction in numbers is expected to largely be achieved through tightening up student visas and the number of unskilled workers coming in.

Across the rest of the country we have seen strong population growth in areas such as the upper North Island and Otago (see chart below), but almost every region has seen its population expand over the past year. The newly formed Labour-NZ First coalition government is looking to both increase the supply of housing and also cut net migration numbers – which theoretically should help bring supply and demand in the market back into balance. Population growth has in large part been driven by record-high net migration levels in the past few years. Net migration has contributed over 2/3rds of the increase in population – with the other 1/3rd due to natural population increase (more births than deaths). Under the new government, the Labour party’s policy of cutting net migration by 20,000-30,000 per year (from the current annual rate of 71,000) appears to be the preferred policy – rather than NZ First’s much more restrictive stance of cutting net migration to an annual rate of 10,000. The reduction in numbers is expected to largely be achieved through tightening up student visas and the number of unskilled workers coming in.

However, our view is that net migration will still remain solid and still elevated by historical standards. Other major governments have tightened up migration policy in the past year, including:

However, our view is that net migration will still remain solid and still elevated by historical standards. Other major governments have tightened up migration policy in the past year, including:

- Australia has increased the stringency of English language tests and citizenship test. Migrants who become permanent residents will now have to wait four years before applying for citizenship – versus one year previously. In addition, New Zealanders in Australia are facing tighter rules around applying for citizenship and access to student loan assistance.

- In the UK, immigration changes have tightened up salary requirements for Tier 2 visas and levied an Immigration Skills Charge for skilled migrants on employers.

These are two of the most common destinations for New Zealanders to move to and hence, with tighter international migration rules and reduced rights while overseas, we expect many New Zealanders to continue to stay put – lowering departure levels. At the same time, for those who can still obtain a visa, New Zealand remains an attractive place to live and work – especially given some of the geo-political tensions in other parts of the globe.

Hence, despite the anticipated changes in migration policy from the NZ government, we expect net migration to remain solid at a pace of 40,000-50,000 in the next couple of years. Net migration gains of this magnitude would still require an additional 15,000+ homes to be built in NZ each year just to compensate for population growth.

Building sector operating at full steam

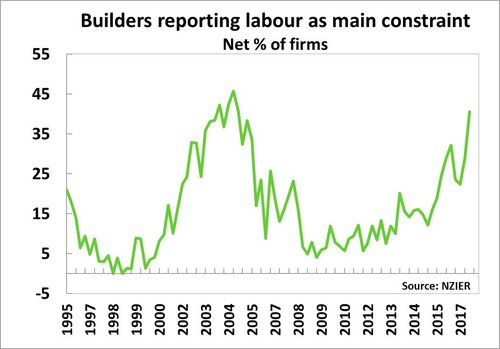

However, we don’t expect to see any sort of quick resolution on supply within the next few years. The new Labour-led government has pledged to build 10,000 new houses a year on average across NZ, with 5,000 of them in Auckland. But the construction industry already appears to be operating at full capacity, with most construction firms reporting a lack of skilled labour as the biggest constraint to increasing production.

The NZ Building and Construction Industry Training Organisation (BCITO) estimates that New Zealand “needs 65,000 new people over the next five years to meet new growth and replace people who leave” in the construction industry. At present, it is estimated that there are about 11,000 apprentices in training – a record number but still not enough to fill the gap. At the same time, a rough estimate of skilled work visas issued in the 2016/17 June year, show that approximately 6,000 migrants entered NZ on a construction-industry related skilled work visa. Labour’s ‘Dole for Apprenticeships’ programme is estimated to increase the number of people in training by 4,000 – although not necessarily entirely in construction and building. In addition, Labour is allowing building firms to hire a skilled tradesperson on a three-year work visa (without having to meet labour market tests) if they take on a local apprentice for each overseas worker they hire – although this will be limited to between 1,000-1,500 at any one time. Adding these pieces of data together points toward clear skill shortages in the industry, but reports suggest that there is also a distinct lack of unskilled workers, which is likely to also be a limiting factor in ramping up building work. Hence, if the government really wants to increase the overall amount of houses getting built each year, they will need to figure out a way to meet these skill shortages. Already the cost of building work has increased significantly in the last few years, with the cost of building new housing up 5.4% yoy, due to the rising cost of labour and materials.

The NZ Building and Construction Industry Training Organisation (BCITO) estimates that New Zealand “needs 65,000 new people over the next five years to meet new growth and replace people who leave” in the construction industry. At present, it is estimated that there are about 11,000 apprentices in training – a record number but still not enough to fill the gap. At the same time, a rough estimate of skilled work visas issued in the 2016/17 June year, show that approximately 6,000 migrants entered NZ on a construction-industry related skilled work visa. Labour’s ‘Dole for Apprenticeships’ programme is estimated to increase the number of people in training by 4,000 – although not necessarily entirely in construction and building. In addition, Labour is allowing building firms to hire a skilled tradesperson on a three-year work visa (without having to meet labour market tests) if they take on a local apprentice for each overseas worker they hire – although this will be limited to between 1,000-1,500 at any one time. Adding these pieces of data together points toward clear skill shortages in the industry, but reports suggest that there is also a distinct lack of unskilled workers, which is likely to also be a limiting factor in ramping up building work. Hence, if the government really wants to increase the overall amount of houses getting built each year, they will need to figure out a way to meet these skill shortages. Already the cost of building work has increased significantly in the last few years, with the cost of building new housing up 5.4% yoy, due to the rising cost of labour and materials.

If we are to increase supply without a significant increase in the number of available construction workers, we will need to get savvier about how we build. For example, a significant shift toward more prefabricated and denser housing could help speed up the building process, reduce the amount of workers required, and in some instances lower the cost of building materials. However, until New Zealanders give up their dream of an individually built house on a quarter-acre section, we expect that the increase in housing supply will continue to lag behind population growth for at least another couple of years.

Affordability issues here to stay

With the housing supply and demand imbalance likely to persist, we don’t expect to see a significant correction in house prices in the near future. However, as mentioned above, affordability constraints are also having an impact on New Zealanders’ ability to get a foot on the property ladder. While this has been a noteworthy constraint in Auckland in recent years, it is increasingly becoming an issue around the rest of the country as well. Unless prices actually start to decline, it will take some time for affordability constraints to ease as incomes rise. We expect to see wage growth pick up from its lacklustre pace of 1.6% yoy in coming years as the labour market continues to tighten.

However, the RBNZ’s tightening of LVR restrictions at the end of 2016 has seen the share of mortgage lending to property investors decline from almost 40% of all lending, down to about 23% currently (see chart below). While credit growth has also shrunk over this time, this has allowed more first home buyers and other households who are trading up, to purchase property.

However, the RBNZ’s tightening of LVR restrictions at the end of 2016 has seen the share of mortgage lending to property investors decline from almost 40% of all lending, down to about 23% currently (see chart below). While credit growth has also shrunk over this time, this has allowed more first home buyers and other households who are trading up, to purchase property.

The other factor that is important to consider is the outlook for mortgage rates in coming years. The Official Cash Rate (OCR) is currently at a record low and that has kept mortgage interest rates near historically low levels. But in the past year, mortgage rates have started to slowly creep higher. We expect to see the RBNZ hike the OCR from the end of 2018 which will put upward pressure on mortgage rates as well. In addition, global central banks are also moving toward tighter monetary policy settings, which put further upward pressure on local rates here.

LVR restrictions a permanent feature?

The RBNZ’s LVR rule changes over the last four years have had a varying impact on the housing market. However, these rules were always supposed to be ‘temporary’ with the idea that LVR restrictions can be used to smooth the peaks and the troughs of a housing market cycle. So this begs the question, at what point will the RBNZ feel comfortable removing LVR restrictions? We don’t expect to see the outright removal of this policy, but if prices decline significantly then we suspect the RBNZ will look at loosening LVR settings. For example, the Bank could increase the percentage of mortgage lending to those with less than a 20% deposit up from currently allowing 10% of all lending, to 15% and then 20% over time. This would still keep the amount of leverage in the housing market lower than that seen prior to the introduction of the rules - when about 30% of some banks’ lending was to those with less than a 20% deposit. A similar approach could be taken for the investor segment of the market.

What does this mean for the economy as a whole?

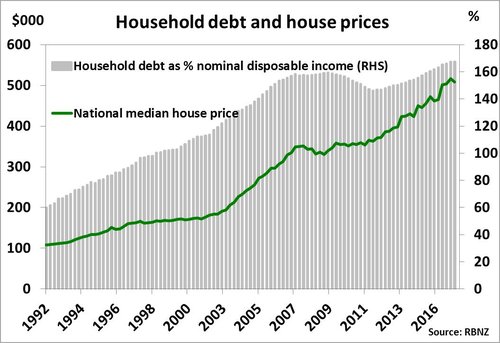

While house prices have been rising since the GFC, so too have household debt levels as people have leveraged up at low interest rates in order to get into the market. As a result the household debt-to-income ratio in NZ has increased to 169% - a record high. With household debt so elevated, increasing mortgage rates will quickly have an impact on household consumption. Overall this feeds into our view that interest rates hikes in New Zealand will be gradual and we don’t expect to see mortgage rates get anywhere near back to the levels we saw pre-GFC – partly because of elevated debt levels in the economy.

While house prices have been rising since the GFC, so too have household debt levels as people have leveraged up at low interest rates in order to get into the market. As a result the household debt-to-income ratio in NZ has increased to 169% - a record high. With household debt so elevated, increasing mortgage rates will quickly have an impact on household consumption. Overall this feeds into our view that interest rates hikes in New Zealand will be gradual and we don’t expect to see mortgage rates get anywhere near back to the levels we saw pre-GFC – partly because of elevated debt levels in the economy.

Studies show that, in the short-term, a rise in household debt tends to boost economic growth at the time – as we have experienced in the last few years. However, over the subsequent 3-5 years, growth is slower than it otherwise would have been. In addition, if the housing market were to experience a sharp correction, then this would have a negative flow-on effect to the broader economy as people rein in spending. While our central view is for house prices to experience a small rebound in the near term and then flat line for a few years, there remains significant policy uncertainty in the wake of a new government.