Being a Department of Conservation dog handler just might be the best job in New Zealand, but no one said it was easy. It can take about 18 months of daily training to become a fully certified dog-handler. We met with two of DOC’s star handlers to find out what it takes to work with the talented pups changing what's possible for New Zealand conservation.

Once certified, handlers still need to train several times a week for the duration of the dog’s working life which is roughly up to 10 years. To train a successful dog, handlers must have experience of working with the target protected or pest species and dog-handling and training experience.

It all starts with good training

Even once a handler is certified they still need to train several times a week for the duration of the dog’s working life, which is roughly up to 10 years. To train a successful dog, handlers must have experience of working with the target protected or pest species, then they also need to have dog-handling and training experience.

Dog handlers train their dogs from day one when they get them – the pups are weaned at 8 weeks and most stay with their handlers for the lifespan of their career. From 6 months old to a year, handlers build confidence and trust with their dogs and socialise them as much as possible by introducing them to different environments and people.

This is also the time when handlers can really establish rapport and bond with their dogs.

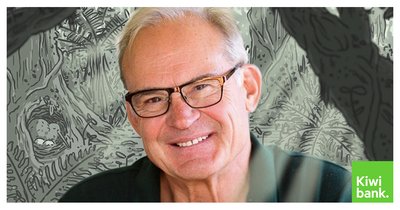

Andrew Glaser, who leads the national Whio Recovery Group, tells us that he likes to look at it from the pup’s perspective: “You’re taking the dogs away from everything they know, their mum and siblings, so by establishing a bond you connect with the dog by playing with them, getting them to smell you, and lying down and letting them climb all over you just like they’d do with their mum. You end up as a surrogate parent.”

Carol Nanning works as a pest detection dog handler in North Head. She lives with her dogs who she says are part of the family. Her two rodent dogs are fully certified: Pai (which means good in Māori) and Piri (which means to cling). Carol and her partner have had both dogs since they were pups. Pai is now 8 and Piri is 4. Both dogs have the same dad, Jak the Ratter, a rather famous conservation dog.

Carol started working as a conservation dog handler in 2012. She, and her partner Fin, had hunting dogs all their working lives until Fin trained up a rodent dog (Jak), and they got hooked. “Fin became a certified dog handler and I would train the pups. I’d worked in conservation for many years and then I was asked to take on the Biosecurity Ranger job in North Head.”

Precious pooches

Every conservation dog is slightly different, some are very willing to please and know what you’re trying to do.

Every conservation dog is slightly different, some are very willing to please and know what you’re trying to do.

Handlers build confidence by rewarding desirable behaviour and through this positive reinforcement, the dogs learn what is expected of them.

Like humans, dogs can have bad days but a good handler will match their discipline methods to the dog’s natural temperament. If they don’t, a dog can get resentful and the talented handlers know that.

"It’s a real delicate balance of social understanding and how dog psyche works."

According to Andrew, handlers must learn to read their dogs and work with their body language which can be as subtle as a raised eyebrow or dropping a hind foot. And if the handler is in a bad mood, the training simply won’t work. “Experienced handlers see it as a journey. You can’t be too impatient and you don’t want to push the dog too hard.”

Before dogs can get into the field to do their thing, they have to demonstrate their competency with the basic commands: stop, come and wait in a prolonged state (up to a minute). This shows that their handlers can control the dog, and demonstrates that the dog is safe around protected species. Both the dog and the handler are assessed by DOC certifiers.

Work hard, play hard

In most cases, dogs live with handlers further enforcing the bond between them, so much so that the dog becomes one of the family.

They work hard, but they also live a life filled with a lot of love.

Andrew has been a dog handler himself for 17 years. He has two certified species detection dogs, Beau and Neo. There are currently 80 dogs (approx.) in the DOC conservation dog programme at the moment, and around 70 handlers some of whom have multiple dogs. Some handlers have multiple dogs because they’re trained on different targets. Beau and Neo are trained on multiple endangered species to keep them working throughout the year.

Andrew’s day with his dogs starts at 6am when they wake him up for coffee. After he’s had his coffee, he lets them run up the beach. They love to run around in the morning and stretch their legs with long looping runs and maybe a good chase of a stick.

“I have to pinch myself sometimes. I think to myself, man, I’ve got a good life. I’ve got my best friend here.”

After that, and if they’re lucky, they’ll get a bone. “If we’re going to work, I get all my gear ready the night before. My dogs know when they see the packs they’re going to be working and they get excited. At 4am they’ll be sitting there waiting, keen as beans! They just can’t wait because they know they’re going to work in the field.” In the field, the dogs are kitted out in working vests and muzzles. Once they’ve found their targets, Andrew lets them have a big roll in the grass. “It’s kind of like their bath.” He also towels them off in his truck.

There are big mattresses in the back to make sure that the journey to and from the fields is as comfortable as possible. “Once we’re home, they become the priority. I check for cuts and abrasions, put creams and ointments to treat any injuries. Then they get a good rub down, a pat, and a sit in the sun.” Andrew believes that seven pats gives them another year, so he makes sure he does that every morning, “It’s one of my rituals.”

Best job ever

Carol’s day also starts at 6 am. After a short walk with Pai, they get into their matching fluro jackets and head to work. “I always allow some time to have a run in a park where I know there are rodents so she can have a hunt.” For Carol, the best part of the job is spending every day with her dogs.

“In my day-to-day, there are parts of the job that are non-negotiable like training, but the hunt is the most exciting thing about running a rodent dog.”

While her quarantine work around the wharves and marinas keeps her quite busy with weekly inspections, she also does pest-free warrants for the major ferries as all New Zealand vessels need to be pest-free warranted.

When Carol arrives at the wharf, she lets Piri do a sweep of the vehicles after introducing herself and her dog to the staff. It takes about an hour to do a proper inspection and Carol notes that often they don’t find anything thanks to the strict protocols ships and ferries adhere to. She lets Piri off her lead but directs her in a systematic way to do a search. “I work to a system. I do the inspection first and if I’ve got time, I plant something for Piri to find on the barge, usually a mouse scented bag.” After the inspection Carol gives her dog lots of praise.

“These dogs love to work, in fact, they’re purpose bred to work. They love nothing more. There’s nothing better than a dog with a job.”

Handlers get incredibly attached to their dogs, to the point where it becomes hard to be away from them. Andrew travels a lot to advocate for the work he does, but when he’s gone, he misses the dogs terribly! “You know, they’re our family. We devote our lives to these dogs and a lot of people don’t understand the commitment to the work we do. We do it because we’re passionate about the work. We love our dogs – the value they add to conservation is incredible. There’s not a lot of it we could do without them. They make the job possible.”

He’s been offered other jobs, but after 17 years in this role, it’s a big part of his life and it’s a passion he wants to share with others, from other handlers to everyday New Zealanders. “We’re recognised as world leaders in our role and we’re able to expand the programme further through the Kiwibank partnership allowing us to make full use of these amazing dog skills.” Before Kiwibank got on board, dogs and handlers were the unsung heroes of conservation work in New Zealand, but now Kiwis are starting to understand the important work they do.

The Conservation Dogs and their talented handlers are active all over New Zealand. You might be lucky enough to meet them at wharves, ferry terminals, island and mainland sanctuaries, in the national parks or perhaps even at your local Kiwibank branch so keep an eye out when you're exploring our backyard! A huge thanks to Andrew for sharing his great photos.

Want to find out more? Stay up to date with the programme by visiting the Dog Programme section on DOC's website or check out Kiwibank’s social media channels.